Understanding Tier 2 in the Integrated Multi-Tiered System of Supports (iMTSS)

The Importance of Tier 2

1. Early Identification and Intervention: One of the primary goals of Tier 2 is to identify and support students who are at risk for academic difficulties early on. Research shows that early intervention is crucial for preventing long-term academic struggles. According to the National Reading Panel (2000), early reading interventions are significantly more effective than later remediation. By providing targeted support at the first sign of difficulty, educators can help prevent small issues from becoming significant obstacles.

2. Preventing the Matthew Effect: The Matthew Effect, coined by Stanovich (1986), refers to the phenomenon where "the rich get richer and the poor get poorer" in terms of reading skills. Students who start with strong reading skills tend to improve at a faster rate, while those with weak skills fall further behind. Tier 2 interventions are designed to prevent this effect by giving struggling readers the support they need to catch up with their peers.

3. Efficient Use of Resources: Tier 2 allows for a more efficient use of educational resources. By providing targeted interventions to small groups of students, schools can address learning gaps without overburdening the system. This targeted approach ensures that students receive the help they need without requiring the more intensive and resource-heavy supports of Tier 3.

What Tier 2 Is Not

Tier 2 is not simply reteaching Tier 1 instruction in the same way or increasing the time a student spends on general curriculum without adjusting how it’s delivered. According to Fuchs, Fuchs, and Compton (2012), effective Tier 2 instruction must be more explicit, more systematic, and more intensive than what students receive in the general education setting. It’s not a “wait and see” model where students are passively monitored—nor is it one-size-fits-all instruction. A student who struggles in Tier 1 needs targeted intervention that directly addresses their unique learning gaps, not just extra exposure to the same material that didn’t work the first time.

Additionally, Tier 2 is not special education or an automatic path to an Individualized Education Program (IEP). The purpose of Tier 2 is to prevent the need for more intensive services by addressing difficulties early and efficiently. IDEA 2004 encourages schools to use scientifically based interventions and progress monitoring as part of the evaluation process, but Tier 2 should never delay a referral to special education when appropriate. Tier 2 must be timely, data-driven, and carefully implemented to be effective—and should not be mistaken for a permanent placement or used as a gatekeeper for accessing special education services.

How Tier 2 Ties into the Science of Reading Best Practices

The science of reading is a body of research that encompasses what is known about how people learn to read. This research has led to evidence-based practices that are effective in teaching reading. Tier 2 interventions, when aligned with these best practices, can significantly enhance reading outcomes for students.

1. Explicit and Systematic Instruction: The science of reading emphasizes the importance of explicit and systematic instruction in foundational reading skills, such as phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Tier 2 interventions often focus on these areas, providing students with clear, direct teaching and practice opportunities.

Research Support: A study by Foorman et al. (2016) found that explicit instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics leads to significant improvements in reading outcomes for struggling readers.

2. Data-Driven Decision Making: Effective Tier 2 interventions rely on ongoing assessment and data analysis to identify students' needs, monitor progress, and adjust instruction as necessary. This data-driven approach ensures that interventions are tailored to each student's specific strengths and weaknesses.

Research Support: The use of curriculum-based measurement (CBM) has been shown to be effective in monitoring student progress and guiding instruction. Fuchs and Fuchs (2006) highlighted the importance of frequent progress monitoring in ensuring the success of interventions.

3. Small Group Instruction: Tier 2 interventions typically involve small group instruction, which allows for more personalized and intensive support. Small groups enable teachers to provide more immediate feedback and to differentiate instruction based on individual student needs.

Research Support: Wanzek and Vaughn (2007) found that small group reading interventions are more effective than whole-class instruction for students with reading difficulties, particularly when the groups are kept to a manageable size.

4. Multisensory Approaches: The science of reading supports the use of multisensory approaches, which engage multiple senses to reinforce learning. This can include visual, auditory, and kinesthetic-tactile activities that help students connect sounds to letters and words.

Research Support: Multisensory teaching methods, such as those used in the Orton-Gillingham approach, have been shown to be effective for students with dyslexia and other reading difficulties (Ritchey & Goeke, 2006).

Implementing Tier 2 Interventions

Effective implementation of Tier 2 interventions requires careful planning and ongoing evaluation. Here are some key steps:

1. Screening and Identification: Universal screening is essential for identifying students who may need Tier 2 support. Screening tools should be reliable and valid, and they should be administered regularly to catch issues early.

2. Designing Interventions: Interventions should be evidence-based and tailored to address the specific needs identified through screening and assessment. They should include explicit, systematic instruction in foundational reading skills and incorporate multisensory teaching methods where appropriate.

3. Progress Monitoring: Regular progress monitoring is crucial for assessing the effectiveness of interventions and making necessary adjustments. This involves frequent, brief assessments that provide data on student progress and inform instructional decisions.

4. Professional Development: Teachers need ongoing professional development to stay current with the latest research and best practices in reading instruction. This training should include strategies for delivering Tier 2 interventions and using data to guide instruction.

5. Family Involvement: Engaging families in the intervention process can enhance student outcomes. Parents and caregivers can support reading development at home through activities that reinforce skills being taught in school.

Challenges and Solutions

Implementing Tier 2 interventions can present challenges, but with thoughtful planning and collaboration, these can be overcome.

1. Resource Limitations: Schools may face limitations in staffing, time, and materials for Tier 2 interventions. Solutions include leveraging existing resources, such as paraprofessionals and volunteers, and seeking grants or other funding opportunities.

2. Fidelity of Implementation: Ensuring that interventions are implemented with fidelity is critical for their success. This requires ongoing training, supervision, and support for teachers, as well as regular observation and feedback.

3. Balancing Interventions with Core Instruction: It's important to ensure that Tier 2 interventions supplement, rather than replace, core instruction. This requires careful scheduling and coordination to ensure that students do not miss out on essential classroom learning.

Tier 2 interventions are a vital component of the iMTSS framework, providing targeted support to students who are at risk for academic difficulties. By aligning these interventions with the science of reading best practices—such as explicit and systematic instruction, data-driven decision making, small group instruction, and multisensory approaches—schools can significantly improve reading outcomes for struggling readers. Ongoing assessment, professional development, and family involvement are essential for the successful implementation of Tier 2 interventions. With the right support in place, all students can achieve reading success and reach their full potential.

Chat Soon-

References

- Fuchs, L. S., & Fuchs, D. (2006). Introduction to response to intervention: What, why, and how valid is it? Reading Research Quarterly, 41(1), 93-99.

- Foorman, B. R., Francis, D. J., Fletcher, J. M., Schatschneider, C., & Mehta, P. (1998). The role of instruction in learning to read: Preventing reading failure in at-risk children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(1), 37-55.

- National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

- Ritchey, K. D., & Goeke, J. L. (2006). Orton-Gillingham and Orton-Gillingham–based reading instruction: A review of the literature. The Journal of Special Education, 40(3), 171-183.

- Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21(4), 360-407.

- Wanzek, J., & Vaughn, S. (2007). Research-based implications from extensive early reading interventions. School Psychology Review, 36(4), 541-561.

What is Reading Fluency?

What is Reading Fluency?

Reading fluency is the ability to read text accurately, quickly, and with appropriate expression. It involves three key components:

- Accuracy: The ability to recognize or decode words correctly.

- Speed: The rate at which a person reads, often measured in words per minute.

- Prosody: The use of appropriate phrasing, intonation, and expression while reading, which contributes to the overall meaning of the text.

Fluency serves as a critical link between word recognition and comprehension. Fluent readers can focus their cognitive resources on understanding the text because they do not have to spend much effort on decoding individual words.

The Importance of Reading Fluency

The National Reading Panel's report underscored the importance of reading fluency for several reasons:

- Foundation for Reading Comprehension: Fluency is closely tied to reading comprehension. Fluent readers can read text smoothly and with understanding, allowing them to focus on the meaning rather than on decoding words. This ability to read effortlessly enables better comprehension and retention of information.

- Improves Academic Performance: Reading fluency is a strong predictor of overall academic performance. Students who read fluently are better able to comprehend texts across various subjects, including science, social studies, and mathematics. This broadens their knowledge base and enhances their ability to perform well academically.

- Enhances Motivation and Engagement: Fluent readers are more likely to enjoy reading and engage in it willingly. The ability to read smoothly and understand text increases a student's confidence and motivation to read, leading to more frequent and prolonged reading experiences.

- Supports Vocabulary Development: Fluent reading exposes students to a wider range of vocabulary. As students read more fluently, they encounter new words in context, which helps them understand and learn these words more effectively.

- Addresses Reading Disabilities: Fluency instruction is particularly beneficial for students with reading disabilities. It provides structured practice and strategies to improve decoding skills, accuracy, and speed, which are essential for overcoming reading challenges.

Current Research on Reading Fluency

Since the publication of the NRP Report, further research has continued to support the importance of reading fluency. Key findings from recent studies include:

- Repeated Reading: Research consistently shows that repeated reading, where students read the same text multiple times, significantly improves reading fluency. This practice helps build accuracy, speed, and prosody, leading to better comprehension.

- Guided Oral Reading: Guided oral reading practices, where students read aloud with immediate feedback and guidance from a teacher or peer, have been found to be highly effective. This approach provides opportunities for students to practice fluency and receive corrective feedback.

- Fluency-Oriented Instruction: Instruction that integrates fluency practice with comprehension activities enhances both fluency and understanding. For example, pairing repeated reading with comprehension questions or discussions helps students see the purpose of fluency in understanding the text.

- Technology Integration: Technology, such as audio books, digital reading programs, and fluency apps, can support fluency development. These tools provide engaging and interactive ways for students to practice fluency and receive instant feedback.

- Differentiated Instruction: Differentiated fluency instruction, tailored to meet the needs of individual students, is crucial. Recognizing that students have varying levels of fluency, personalized approaches ensure that all students receive appropriate practice and support.

Practical Strategies for Developing Reading Fluency

To maximize the effectiveness of reading fluency instruction, educators should incorporate evidence-based strategies into their teaching practices. Here are some practical tips:

- Repeated Reading: Implement repeated reading practices where students read the same text multiple times until they achieve a certain level of fluency. This method is particularly effective for improving speed and accuracy.

- Guided Oral Reading: Provide guided oral reading opportunities where students read aloud with feedback from a teacher, peer, or parent. This practice helps students improve their fluency through immediate corrective feedback and modeling of fluent reading.

- Model Fluent Reading: Model fluent reading by reading aloud to students regularly. Demonstrating how fluent reading sounds, including appropriate pacing, expression, and phrasing, provides students with a clear example to emulate.

- Use of Technology: Incorporate technology to support fluency practice. Tools such as audio books, digital reading platforms, and fluency apps offer engaging ways for students to practice and improve their fluency skills.

- Reader's Theater: Engage students in Reader's Theater, where they read and perform scripts based on literature. This activity emphasizes expressive reading and provides a fun and interactive way to practice fluency.

- Fluency-Oriented Instruction: Integrate fluency practice with comprehension activities. For example, after repeated readings, engage students in discussions or ask comprehension questions to reinforce the connection between fluency and understanding.

- Differentiated Fluency Practice: Differentiate fluency instruction to meet the diverse needs of learners. Provide additional practice and support for struggling readers and challenge advanced readers with more complex texts.

- Track Progress: Monitor and track students' fluency progress regularly. Use fluency assessments, such as timed readings and fluency checklists, to identify areas of improvement and adjust instruction accordingly.

Case Study: Effective Fluency Instruction in Action

To illustrate the practical application of these strategies, let’s look at a case study from a fourth-grade classroom.

Classroom Context:

Ms. Johnson is a fourth-grade teacher who prioritizes reading fluency in her literacy instruction. She uses a combination of repeated reading, guided oral reading, and technology to enhance her students' fluency skills.

Implementation:

- Repeated Reading: Ms. Johnson implements repeated reading sessions three times a week. Students select a passage at their reading level and read it multiple times, aiming to improve their accuracy and speed with each reading.

- Guided Oral Reading: During guided reading groups, Ms. Johnson provides opportunities for students to read aloud. She listens to each student, offering immediate feedback and modeling fluent reading.

- Modeling Fluent Reading: Ms. Johnson reads aloud to her students daily, demonstrating fluent reading with appropriate expression and pacing. She discusses her reading process and encourages students to mimic her fluency.

- Use of Technology: Ms. Johnson integrates technology by using digital reading programs and fluency apps. Students use these tools during independent reading time to practice fluency and receive instant feedback.

- Reader's Theater: Once a month, Ms. Johnson organizes Reader's Theater activities. Students rehearse and perform scripts, focusing on expressive reading and teamwork.

- Fluency-Oriented Instruction: Ms. Johnson pairs fluency practice with comprehension activities. After repeated readings, she engages students in discussions and comprehension questions to reinforce understanding.

- Differentiated Practice: Recognizing the diverse needs of her students, Ms. Johnson differentiates fluency instruction. Struggling readers receive additional practice and support, while advanced readers work on more challenging texts.

- Progress Tracking: Ms. Johnson regularly assesses her students' fluency using timed readings and fluency checklists. She tracks their progress and adjusts her instruction based on the assessment results.

Outcomes:

By the end of the school year, Ms. Johnson’s students demonstrate significant improvement in their reading fluency. They read more accurately and quickly and with better expression. This improvement in fluency translates into better reading comprehension and overall academic performance. Ms. Johnson’s systematic and engaging approach to fluency instruction has helped her students become more confident and proficient readers.

Reading fluency is a vital component of literacy development, as highlighted by the National Reading Panel and supported by ongoing research. It provides the necessary foundation for reading comprehension, academic success, motivation, and overall language development. Effective fluency instruction, delivered through explicit, systematic, and engaging methods, can significantly improve students' reading outcomes.

Teachers play a crucial role in fostering reading fluency. By incorporating evidence-based strategies and providing ample practice opportunities, we can help ensure that all students develop the fluency skills necessary for reading success. As research continues to evolve, the importance of reading fluency remains clear, underscoring its role as a cornerstone of literacy education.

Looking Fluency for Additional Blog Posts:

- How I Use Games to Increase Students’ Phonics Word Level Fluency

- How I Increased Reading Fluency Scores

References

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read: An Evidence-Based Assessment of the Scientific Research Literature on Reading and Its Implications for Reading Instruction. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Hudson, R. F., Lane, H. B., & Pullen, P. C. (2005). Reading fluency assessment and instruction: What, why, and how? The Reading Teacher, 58(8), 702-714.

- Kuhn, M. R., & Stahl, S. A. (2003). Fluency: A review of developmental and remedial practices. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 3-21.

- Rasinski, T. V. (2012). Why reading fluency should be hot! The Reading Teacher, 65(8), 516-522.

- Samuels, S. J. (2006). Toward a model of reading fluency. In S. J. Samuels & A. E. Farstrup (Eds.), What Research Has to Say About Fluency Instruction (pp. 24-46). International Reading Association.

- Paige, D. D. (2011). 16 Minutes of “Eyes-on-Text” can make a difference: Whole-class choral reading as an adolescent fluency strategy. Reading Horizons, 51(1), 1-18.

What is Reading Comprehension? Why do we need it?

Reading comprehension is the ability to understand, interpret, and analyze texts. It is a fundamental skill that underpins successful learning and academic achievement. The National Reading Panel (NRP) identified reading comprehension as one of the five critical components of effective reading instruction, emphasizing its central role in literacy. This blog post explores what reading comprehension is, why it is important, and how current research continues to highlight its essential role in literacy and overall academic success.

What is Reading Comprehension?

Reading comprehension involves multiple processes that enable readers to make sense of written text. These processes include:

- Decoding: The ability to recognize and process written words.

- Vocabulary Knowledge: Understanding the meanings of words and how they are used in context.

- Fluency: The ability to read text accurately and smoothly, which allows for better focus on understanding the text.

- Background Knowledge: Prior knowledge and experiences that readers bring to a text, which help them make connections and infer meaning.

- Comprehension Strategies: Techniques that readers use to make sense of text, such as summarizing, questioning, predicting, and visualizing.

Effective reading comprehension is not just about reading the words on a page but involves an active engagement with the text, leading to a deeper understanding and the ability to apply the information.

The Importance of Reading Comprehension

The National Reading Panel's report highlighted several reasons why reading comprehension is crucial:

- Foundation for Academic Success: Reading comprehension is essential for academic success across all subjects. Students who can understand and interpret text are better equipped to learn new information, follow instructions, and engage in critical thinking. This skill is foundational for subjects such as science, social studies, and mathematics.

- Critical Thinking and Problem Solving: Reading comprehension fosters critical thinking and problem-solving skills. By understanding and analyzing texts, students learn to evaluate information, make inferences, and draw conclusions. These skills are vital for academic achievement and real-world problem-solving.

- Lifelong Learning: Reading comprehension is a gateway to lifelong learning. Individuals who can comprehend texts effectively are more likely to continue learning throughout their lives. This ability opens up opportunities for personal growth, career advancement, and informed citizenship.

- Enhanced Communication Skills: Effective reading comprehension contributes to better communication skills. Understanding complex texts and diverse perspectives helps individuals articulate their thoughts and ideas clearly and persuasively, both in writing and speaking.

- Cognitive Development: Reading comprehension supports cognitive development by engaging the brain in complex processes of understanding, analyzing, and synthesizing information. This engagement enhances cognitive functions such as memory, attention, and executive functioning.

Current Research on Reading Comprehension

Since the publication of the NRP Report, further research has continued to support the importance of reading comprehension. Key findings from recent studies include:

- Importance of Background Knowledge: Research emphasizes the role of background knowledge in reading comprehension. Readers with relevant prior knowledge about a topic are better able to understand and retain new information. This finding underscores the importance of integrating content knowledge with reading instruction.

- Role of Vocabulary: Vocabulary knowledge is a critical component of reading comprehension. Studies show that a rich vocabulary enhances readers' ability to understand and interpret text. Effective vocabulary instruction, therefore, is essential for improving reading comprehension.

- Use of Comprehension Strategies: Teaching comprehension strategies explicitly is highly effective. Strategies such as summarizing, questioning, predicting, and visualizing help readers actively engage with the text and improve their understanding.

- Impact of Motivation and Engagement: Motivation and engagement play significant roles in reading comprehension. Students who are motivated and engaged in reading are more likely to invest the effort required to understand complex texts. Creating a motivating and engaging reading environment is crucial for fostering comprehension.

- Technology Integration: Technology can support reading comprehension by providing interactive and engaging reading experiences. Digital tools, such as e-books and reading apps, offer features like annotations, multimedia elements, and interactive questions that enhance comprehension.

Practical Strategies for Developing Reading Comprehension

To maximize the effectiveness of reading comprehension instruction, educators should incorporate evidence-based strategies into their teaching practices. Here are some practical tips:

- Activate Prior Knowledge: Help students activate their prior knowledge before reading. Discuss what they already know about the topic and how it relates to the new text. This strategy helps students make connections and set a purpose for reading.

- Teach Vocabulary Explicitly: Provide explicit vocabulary instruction to enhance students' understanding of keywords and phrases in the text. Use various methods, such as word maps, context clues, and direct teaching, to build vocabulary knowledge.

- Use Comprehension Strategies: Teach students specific comprehension strategies, such as summarizing, questioning, predicting, and visualizing. Model these strategies during read-alouds and guided reading sessions, and provide opportunities for students to practice them independently.

- Encourage Active Reading: Encourage students to engage in active reading by annotating the text, asking questions, and making predictions. Use graphic organizers and note-taking strategies to help students organize their thoughts and track their understanding.

- Foster a Love of Reading: Create a motivating and engaging reading environment. Provide a diverse selection of reading materials that cater to students' interests and reading levels. Encourage independent reading and provide time for students to share and discuss what they have read.

- Integrate Technology: Incorporate technology to enhance reading comprehension. Use digital tools and resources, such as e-books, interactive reading apps, and online discussion forums, to provide engaging and interactive reading experiences.

- Differentiated Instruction: Differentiate reading comprehension instruction to meet the diverse needs of learners. Provide additional support for struggling readers and challenge advanced readers with more complex texts and higher-order thinking tasks.

- Monitor Progress: Regularly assess students' reading comprehension skills using various assessment tools, such as quizzes, written responses, and comprehension questions. Use the assessment data to inform instruction and provide targeted support.

Case Study: Effective Reading Comprehension Instruction in Action

To illustrate the practical application of these strategies, let’s look at a case study from a fifth-grade classroom.

Classroom Context:

Mr. Anderson is a fifth-grade teacher who prioritizes reading comprehension in his literacy instruction. He uses a combination of explicit strategy instruction, vocabulary building, and engaging activities to enhance his students' comprehension skills.

Implementation:

- Activate Prior Knowledge: Before reading a new text, Mr. Anderson engages students in a discussion about what they already know about the topic. He encourages them to share their experiences and make connections to the text.

- Teach Vocabulary Explicitly: Mr. Anderson introduces key vocabulary words before reading. He uses word maps and context clues to help students understand the meanings and uses of these words. He also encourages students to use the new vocabulary in their writing and discussions.

- Use Comprehension Strategies: Mr. Anderson teaches specific comprehension strategies, such as summarizing, questioning, predicting, and visualizing. He models these strategies during read-alouds and guided reading sessions, and provides opportunities for students to practice them independently.

- Encourage Active Reading: Mr. Anderson encourages students to engage in active reading by annotating the text, asking questions, and making predictions. He uses graphic organizers and note-taking strategies to help students organize their thoughts and track their understanding.

- Foster a Love of Reading: Mr. Anderson creates a motivating and engaging reading environment. He provides a diverse selection of reading materials that cater to students' interests and reading levels. He encourages independent reading and provides time for students to share and discuss what they have read.

- Integrate Technology: Mr. Anderson integrates technology by using digital tools and resources, such as e-books, interactive reading apps, and online discussion forums. These tools provide engaging and interactive reading experiences for students.

- Differentiated Instruction: Mr. Anderson differentiates reading comprehension instruction to meet the diverse needs of his students. He provides additional support for struggling readers and challenges advanced readers with more complex texts and higher-order thinking tasks.

- Monitor Progress: Mr. Anderson regularly assesses his students' reading comprehension skills using various assessment tools, such as quizzes, written responses, and comprehension questions. He uses the assessment data to inform his instruction and provide targeted support.

Outcomes:

By the end of the school year, Mr. Anderson’s students demonstrate significant improvement in their reading comprehension skills. They are better able to understand, interpret, and analyze texts. This improvement in comprehension translates into better overall academic performance and increased confidence in their reading abilities. Mr. Anderson’s systematic and engaging approach to reading comprehension instruction has helped his students become more proficient and motivated readers.

Reading comprehension is a vital component of literacy development, as highlighted by the National Reading Panel and supported by ongoing research. It provides the necessary foundation for academic success, critical thinking, lifelong learning, and effective communication. Effective comprehension instruction, delivered through explicit, systematic, and engaging methods, can significantly improve students' reading outcomes.

Teachers play a crucial role in fostering reading comprehension. By incorporating evidence-based strategies and providing ample practice opportunities, they can help ensure that all students develop the comprehension skills necessary for reading success. As research continues to evolve, the importance of reading comprehension remains clear, underscoring its role as a cornerstone of literacy education.

References

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read: An Evidence-Based Assessment of the Scientific Research Literature on Reading and Its Implications for Reading Instruction. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Duke, N. K., & Pearson, P. D. (2002). Effective practices for developing reading comprehension. In A. E. Farstrup & S. J. Samuels (Eds.), What Research Has to Say About Reading Instruction (pp. 205-242). International Reading Association.

- Pressley, M. (2006). Reading Instruction That Works: The Case for Balanced Teaching (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Snow, C. E. (2002). Reading for Understanding: Toward an R&D Program in Reading Comprehension. RAND Corporation.

- Shanahan, T., Callison, K., Carriere, C., Duke, N. K., Pearson, P. D., Schatschneider, C., & Torgesen, J. (2010). Improving Reading Comprehension in Kindergarten Through 3rd Grade: A Practice Guide (NCEE 2010-4038). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

- McKeown, M. G., & Beck, I. L. (2006). Encouraging young children’s language interactions with stories. In D. K. Dickinson & S. B. Neuman (Eds.), Handbook of Early Literacy Research (Vol. 2, pp. 281-294). Guilford Press.

What is Vocabulary Development?

Vocabulary development is a critical component of literacy education, essential for reading comprehension and overall academic success. The National Reading Panel (NRP) highlighted vocabulary as one of the five key areas of reading instruction, underscoring its importance in helping children understand and engage with text. This blog post explores vocabulary development, why it is important, and how current research emphasizes its crucial role in reading and academic achievement.

What is Vocabulary Development?

Vocabulary development refers to how we acquire and expand our knowledge of words and meanings. It involves not only learning new words but also deepening the understanding of already known words. Vocabulary can be categorized into four types:

Listening Vocabulary: Words we understand when others speak. Speaking Vocabulary: Words we use when we speak. Reading Vocabulary: Words we recognize and understand when we read. Writing Vocabulary: Words we use in writing. Effective vocabulary development involves both direct and indirect methods. Direct vocabulary instruction includes explicit teaching of specific words and their meanings, while indirect vocabulary development occurs through exposure to rich language experiences, such as reading, conversation, and interactive activities. The Importance of Vocabulary Development The National Reading Panel's report emphasized the importance of vocabulary development for several reasons: Foundation for Reading Comprehension: Vocabulary knowledge is a fundamental building block for reading comprehension. Understanding the meanings of words allows readers to make sense of the text and engage with its content. Without a strong vocabulary, readers struggle to grasp the full meaning of what they read.- Academic Success: A robust vocabulary is linked to academic success across all subjects. Students with extensive vocabularies are better able to understand complex texts, follow instructions, and engage in classroom discussions. This advantage extends beyond language arts to subjects like science, social studies, and mathematics.

- Language Development: Vocabulary development is crucial for overall language development. It enhances communication skills, enabling individuals to express themselves clearly and effectively. A rich vocabulary also supports listening and speaking skills, contributing to better social interactions and relationships.

- Critical Thinking and Cognitive Skills: A well-developed vocabulary enhances critical thinking and cognitive skills. Knowing a variety of words allows individuals to think more precisely and creatively, as they can select the most appropriate words to express their thoughts and ideas.

- Closing the Achievement Gap: Vocabulary development plays a significant role in closing the achievement gap associated with socioeconomic status. Children from lower-income families often enter school with smaller vocabularies compared to their peers from higher-income families. Effective vocabulary instruction can help bridge this gap and promote equity in education.

Current Research on Vocabulary Development

Since the publication of the NRP Report, further research has continued to support the importance of vocabulary development. Key findings from recent studies include:

- Incidental Vocabulary Learning: Research highlights the significance of incidental vocabulary learning, which occurs through exposure to rich and varied language experiences. Reading widely, engaging in conversations, and interactive play are effective ways to enhance vocabulary development.

- Direct and Explicit Instruction: While incidental learning is important, direct and explicit vocabulary instruction is also crucial. Teaching specific words and strategies for understanding and remembering them can significantly enhance vocabulary acquisition.

- Importance of Early Intervention: Early vocabulary development is predictive of later reading success. Children who enter school with strong vocabularies are more likely to become proficient readers. Early intervention programs that focus on vocabulary development can have long-lasting positive effects on literacy outcomes.

- Role of Technology: Technology can play a valuable role in vocabulary development. Educational apps, interactive e-books, and online resources can provide engaging and effective vocabulary instruction and practice.

- Cultural and Linguistic Diversity: Research emphasizes the importance of considering cultural and linguistic diversity in vocabulary instruction. Effective programs recognize and build on the linguistic backgrounds of students, incorporating culturally relevant materials and practices.

Practical Strategies for Vocabulary Development

- Explicit Vocabulary Instruction: Provide explicit instruction on specific words and their meanings. Use direct teaching methods, such as introducing new words before reading a text, explaining their meanings, and providing examples and non-examples.

- Contextual Learning: Teach vocabulary in context. Use rich and varied texts to introduce new words and provide opportunities for students to encounter and use these words in meaningful contexts. Contextual learning helps students understand how words function in different situations.

- Interactive Read-Alouds: Conduct interactive read-alouds where teachers or parents read books aloud and engage students in discussions about the text. Highlight and discuss new vocabulary words, ask questions, and encourage students to use the new words in their responses.

- Word Learning Strategies: Teach students strategies for learning new words, such as using context clues, analyzing word parts (prefixes, suffixes, and root words), and using dictionaries and thesauruses. Encourage students to be curious about words and to actively seek out new vocabulary.

- Repetition and Review: Provide multiple exposures to new words through repetition and review. Use various activities and exercises to reinforce vocabulary learning, such as word games, flashcards, and writing exercises. Frequent practice helps solidify word knowledge.

- Engage in Rich Conversations: Engage students in rich conversations that involve using new vocabulary words. Encourage students to express their thoughts and ideas using the words they are learning. Discussions, debates, and collaborative projects provide opportunities for meaningful language use.

- Use of Technology: Incorporate technology to enhance vocabulary instruction. Educational apps, online games, and interactive e-books can provide engaging and effective vocabulary practice. Technology can also provide personalized learning experiences tailored to individual students' needs.

Case Study: Effective Vocabulary Instruction in Action

- Explicit Instruction: Ms. Thompson begins each week by introducing a set of new vocabulary words related to the upcoming unit of study. She provides definitions, examples, and non-examples of each word and engages students in discussions about their meanings.

- Contextual Learning: During reading sessions, Ms. Thompson selects texts that include the target vocabulary words. She conducts interactive read-alouds, pausing to discuss the words in context and encouraging students to make connections between the words and their own experiences.

- Word Learning Strategies: Ms. Thompson teaches her students strategies for learning new words, such as using context clues and analyzing word parts. She models these strategies during reading and writing activities and provides opportunities for students to practice them.

- Repetition and Review: Throughout the week, Ms. Thompson incorporates various activities to reinforce the target vocabulary words. Students play word games, create flashcards, and participate in writing exercises that require them to use the new words.

- Rich Conversations: Ms. Thompson fosters a classroom environment where rich conversations are encouraged. She engages students in discussions, debates, and collaborative projects that involve using the target vocabulary words. Students are encouraged to use the new words in their oral and written responses.

- Use of Technology: Ms. Thompson integrates technology into her vocabulary instruction. She uses educational apps and online games that provide interactive vocabulary practice. Students also have access to e-books that include vocabulary-building features.

Looking for Additional vocabulary blog posts:

Vocabulary Development Strategies Building Vocabulary and Oral Language Why Unlocking Vocabulary is Key to Bridging Gaps for Students The Importance of Oral Language for ELL Students in Reading and WritingReferences

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read: An Evidence-Based Assessment of the Scientific Research Literature on Reading and Its Implications for Reading Instruction. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction. Guilford Press.

- Nagy, W. E., & Scott, J. A. (2000). Vocabulary processes. In M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.), Handbook of Reading Research (Vol. 3, pp. 269-284). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Neuman, S. B., & Dwyer, J. (2009). Missing in action: Vocabulary instruction in pre‐K. The Reading Teacher, 62(5), 384-392.

- Snow, C. E., & Kim, Y. S. (2007). Large problem spaces: The challenge of vocabulary for English language learners. In R. K. Wagner, A

What is the National Reading Panel Report?

If we are to truly understand the shift from "Balanced Literacy" or "Whole Language" to the "Science of Reading" we have to understand where it restarted.

In the late 1990s, the National Reading Panel (NRP) was convened by the U.S. Congress to evaluate the effectiveness of different approaches to teaching children how to read. The goal was to provide a clear, evidence-based understanding of the best practices in reading instruction. The resulting report, published in 2000, has profoundly impacted reading education in the United States and beyond.

The Formation and Mission of the National Reading Panel

The National Reading Panel was established in 1997 as part of the federal Reading Excellence Act. The panel comprised 14 members, including leading scientists in reading research, representatives of colleges of education, reading teachers, educational administrators, and parents. Their mission was to assess the effectiveness of various approaches to reading instruction by reviewing existing research studies.

Methodology

The NRP's methodology was rigorous and systematic. The panel focused on studies that met high standards of scientific research, including randomized control trials and other well-designed experiments. The panel reviewed over 100,000 studies conducted since 1966 and 10,000 earlier studies. Their review process culminated in the identification of five critical areas of reading instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and text comprehension.

Key Findings

Phonemic Awareness: Phonemic awareness is the ability to hear, identify, and manipulate individual sounds—phonemes—in spoken words. This skill is foundational for learning to read. The NRP found that teaching phonemic awareness significantly improves children’s reading skills, including word reading, reading comprehension, and spelling.

Phonics: Phonics instruction teaches the relationship between letters and sounds, enabling readers to decode words. The panel found that systematic and explicit phonics instruction is more effective than non-systematic or no phonics instruction. This approach is particularly beneficial for kindergarteners and first graders, as it helps them develop early reading skills that are crucial for later success.

Fluency: Reading fluency is the ability to read with speed, accuracy, and proper expression. The NRP highlighted the importance of guided oral reading practices in developing fluency. Students who read aloud with feedback and guidance from teachers, parents, or peers show significant improvements in reading fluency and overall reading achievement.

Vocabulary: A robust vocabulary is essential for reading comprehension. The NRP found that vocabulary should be taught both directly and indirectly. Direct vocabulary instruction involves teaching specific words, while indirect instruction involves exposing students to new words through reading and conversation. Both methods are necessary to help students understand and use new vocabulary in context.

Text Comprehension: Text comprehension is the ultimate goal of reading—it involves understanding and interpreting what is read. The NRP identified several strategies that improve comprehension, including:

- Monitoring comprehension: Teaching students to be aware of their understanding of the text.

- Using graphic organizers: Visual aids that help students organize and relate information from the text.

- Answering questions: Encouraging students to answer questions about the text to improve understanding.

- Generating questions: Teaching students to ask their own questions about the text.

- Summarizing: Helping students identify the main ideas and summarize the content.

Implications for Teaching

The findings of the National Reading Panel have significant implications for reading instruction. Here are some practical ways that educators can implement these findings in the classroom:

Balanced Literacy Programs: The NRP's findings support a balanced approach to literacy instruction, integrating various methods to address the five critical areas. Educators should provide systematic and explicit instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics, while also promoting fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension through diverse activities and reading materials.

Professional Development: Teachers need ongoing professional development to stay informed about the best practices in reading instruction. Training programs should focus on the five key areas identified by the NRP and provide teachers with practical strategies for implementing these in their classrooms.

Early Intervention: Early identification and intervention for struggling readers are crucial. By addressing reading difficulties early, educators can prevent long-term reading problems. The NRP's findings underscore the importance of early instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics to build a strong foundation for future reading success.

Parental Involvement: Parents play a vital role in their children's reading development. Schools should encourage parents to engage in their children's reading activities and provide them with strategies to support reading at home. This can include reading aloud together, discussing books, and providing access to a variety of reading materials.

Use of Technology: Technology can be a valuable tool in reading instruction. Interactive software, e-books, and online resources can provide additional practice in phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Educators should integrate technology in a way that complements traditional teaching methods.

Criticisms and Controversies

While the National Reading Panel Report has been widely influential, it has also faced criticisms and controversies. Some educators and researchers argue that the panel's focus on certain methodologies, such as phonics, downplays other important aspects of reading instruction, such as whole language approaches and the role of motivation in reading. Additionally, some critics contend that the report's emphasis on quantitative research overlooks the insights that qualitative studies can provide.

Continuing Impact and Relevance

Despite these criticisms, the NRP Report remains a cornerstone of reading instruction policy and practice. Its influence is evident in the widespread adoption of balanced literacy programs and the emphasis on evidence-based teaching strategies. Furthermore, the report has spurred ongoing research into effective reading instruction, contributing to the evolving understanding of how children learn to read.

In recent years, the science of reading has continued to advance, building on the foundation laid by the NRP. New research has further explored the cognitive processes involved in reading, the impact of socio-economic factors on reading development, and the most effective ways to support diverse learners. Educators and policymakers continue to rely on the principles outlined in the NRP Report while adapting to new findings and changing educational contexts.

The National Reading Panel Report represents a pivotal moment in the field of reading education. Its comprehensive review of research provided a clear, evidence-based framework for effective reading instruction, emphasizing the importance of phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. While it has faced criticisms, its impact on educational policy and practice is undeniable. As the science of reading continues to evolve, the NRP Report remains a valuable resource for educators, guiding the way toward more effective and inclusive reading instruction.

This is the beginning of a new series on the Science of Reading. The Science of Reading impacts how everyone including special education teachers teach reading to students regardless of their disability. The difference is the accommodations and modifications we make to help students access the material.

Chat Soon-

References

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read: An Evidence-Based Assessment of the Scientific Research Literature on Reading and Its Implications for Reading Instruction. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Shanahan, T. (2003). The National Reading Panel Report: Practical Advice for Teachers. Learning Point Associates.

Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (1998). Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children. National Academy Press.

The NRP Report's enduring legacy underscores the importance of rigorous, evidence-based approaches to reading instruction, ensuring that all children have the opportunity to become proficient and enthusiastic readers.

Why Unlocking Vocabulary is Key to Bridging the Gap for Students

The hard thing about waiting three months for iReady's classroom diagnostic data is not knowing how students will do after 10 weeks of intervention.

My state and building use iReady diagnostics three times a year for READ Plans and intervention data. (more on come on iReady-both loves and dislikes)

As a special education teacher, I only use this data to compare students to their peer group and see what kind of gains they had over the year. (I have a whole blog post coming on how my building uses iReady.)

My building relies on this information to make predictions about State testing outcomes and interventions.

For me, I look at the overall gains my students make on the five categories assessed each time. This year, I made a huge shift to building and creating a solid foundation in phonemic awareness and phonics.

The macro data showed students made huge gains when using both Heggerty and Yoshimoto Orton-Gillingham. We lived in controlled decodable and built vocabulary through morphology.

What didn’t improve???

Student’s vocabulary

On iReady, students’ scores either dropped or maintained.

I’m the first to tell you that you should never, ever make significant instructional decisions on a single piece of data. It could take you off a cliff.

But if you layer in IEP goal data and it shows everyone either made or is on target to meet their goals well within their IEP cycle …

Could layering in something, not a change continue that growth????

Could it support and build students’ vocabulary and not have all the growth drop off???

Why Focus on Vocabulary

When I explain the five reading components to parents, I use a pyramid. Phonemic awareness and phonics are the base of the pyramid. With vocabulary and comprehension coming after. Fluency is needed across all.

To get to the top of the pyramid, word-level comprehension is needed before moving to sentence, paragraph, chapter, etc. You see where it goes.But what happens when you have weak word-level vocabulary????

What then? Let me explain how I landed here ...

All my phonics kiddos were placed in Orton-Gillingham. As the year progressed, the pacing of these groups slowed. In some cases stopping for a week or so on a concept, or phonogram or just working to get them unconfused. (English is so confusing.)

As lessons got more complex and the more layers students had to work with the more, I noticed other holes. Looking back at my lesson notes and comments about student progress within lessons it became more obvious that vocabulary was one thing students were struggling with.

To be clear, I'm not talking about Tier 3 subject-specific words. I'm talking about Tier 1 words--like chair, boil, broil, etc. (here is my previous post on Vocabulary Tiers)

Yes, about half of those I pull for OG do receive pull-out language support from a Speech-Language Pathologist.

The funny (or head-banging) thing about all their iReady Vocabulary score was the “can dos” all said to teach 5 words and all through read-aloud. (This is a great idea for classroom teachers; not so much for specialists.)

What Does the Research Say

The Science of Reading (SoR) is an evidence-based approach to teaching reading that is grounded in research from cognitive psychology, linguistics, and neuroscience. It emphasizes the importance of systematically teaching foundational skills to help students become proficient readers. One crucial aspect is phonemic awareness, which involves recognizing and manipulating individual sounds in spoken words.

By explicitly teaching students to understand the connection between letters and sounds through phonics instruction, they can decode words and read fluently. It's essential to provide activities that engage students in segmenting, blending, and manipulating sounds in words to strengthen their phonemic awareness and phonics skills.

Phonemic awareness refers to the ability to identify and manipulate individual sounds in spoken words. It is a critical skill that helps students understand the connection between letters and sounds. Phonics instruction teaches students the relationship between letters and sounds, enabling them to decode words and read fluently. Teachers should provide explicit instruction in these skills, using activities that involve segmenting, blending, and manipulating sounds in words.

Fluency is the ability to read accurately, quickly, and with expression. It is developed through repeated practice and exposure to a wide range of texts. Teachers can support fluency by providing opportunities for independent reading, modeling fluent reading, and using strategies like echo reading or choral reading. Vocabulary instruction is also crucial for reading comprehension. Teachers should explicitly teach new words, provide context clues, and encourage students to use strategies like word analysis and context to understand unfamiliar words.Comprehension involves understanding and making meaning from text. Teachers can support comprehension by explicitly teaching strategies such as predicting, questioning, summarizing, and making connections. These strategies help students engage with the text, monitor their understanding, and make inferences. It is also essential to promote metacognition, encouraging students to think about their thinking and monitor their comprehension. By incorporating these strategies into instruction, teachers can help students become active and proficient readers.

What Does this Mean

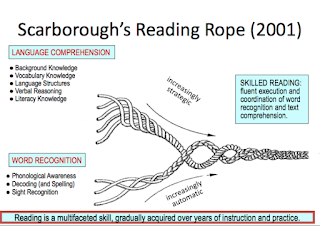

SoR and Scarborough's Rope Model of Reading bring a new light to an old question surrounding phonics and vocabulary. The question is how to layer something in that doesn’t take away from the gains students have made.

I don’t know why this group of students have a weak vocabulary. I could blame COVID–these students were remote and hybrid during COVID. It could be the lack of direct, explicit instruction surrounding Tier 1 and Tier 2 vocabulary. Or it could be the lack of helping students make connections to previously taught vocabulary to new words.

Coming this semester, I’ll share how I plan to attack this and build students’ Tier 1 and Tier 2 vocabulary. I hope to find actionable, tangible ways for students to make gains that don’t take tons of time to get the most bang for my buck as a special education teacher all while doing my job as their special education teacher.

Chat soon-

How I use games to increase students' phonics word level fluency

I sat with my grade level team, reviewing this month’s oral reading fluency data and they could not stop asking me how I moved my group.

In a word – games.

The team had decided to work on accuracy instead of words correct. (I’m not sure there is a great way to increase reading fluency but okay I’m in.) Sometimes starting small is way better than not starting at all and this group has never ventured into the world of using one's data for anything.

So…

This year, grade-level teams are working with our Coach to create monthly data-based goals. We just started using Benchmark Advanced, so teams are looking at all the reading data and making a decision on a long and short-term plan. (For most of the teams I work with–this is the 1st time they have really looked at and done anything with their classroom data.)

This one, as much as I’m shaking my head, I can see a place where I can layer in additional fluency work at the word level with their students and not sacrifice fidelity.

Over the years, I have moved the oral reading fluency scores in a variety of ways. I have never found something that works with most of the students I support for reading. From repeated readings to focusing on specific words, nothing works for all the students in a group.

All my reading groups this year are OG. I live and breathe OG, which means there is a precise lesson plan and very little room to add “other” things. I’m not sure how many really get this. This year, teachers want me to fix everything.

I use Yoshimoto. I really love the flexibility it gives me. I dislike the amount of flexibility it gives me but I can lay out each group's scope and sequence and add my “others” as I need to. Mind you within reason.

Last year, I began working in very specific game days to target word-level fluency. These days tended to be on Fridays (aka Fun Friday). When a Game Tub in tow, students played Crocodile Dentist and Squeaky Squirrel.

Slowly, the sounding out loud stopped. The confidence in the learning target increased. Slowly, the syllable understanding increased. And then the accuracy scores changed. Then the big daddy of them all, the iReady Phonics scores started to move.

Now, was this all by adding game time to their practice do this. I have no way of knowing. But what I do know is that if students are engaged and motivated then everything falls into place.

Reflecting on this growth over the summer, led me to add phrases and sentences based on the skill being taught. You can find my game pieces in my store to begin building self-confidence, language skills, and word-level fluency in your students.

My students do have their favorites but I make a point to rotate them about every month.

The cool thing about all of the game pieces is that it is super easy to differentiate the cards depending on who is in the group and what each student needs to work on.

Nothing like being able to stack the deck. lol

ROAR–CVC, CCVC, CVCC is built using pictures to support the words from Smarty Symbols but you also get cards with no pictures.

You can play with just CVC or CVCC with and without pictures.

OR

When I have a group working on Five and Six sounds. I pull out Melt. Then students can work on real and nonsense words. You can add easier words to build fluency or a couple of compound words to make it more interesting.

OR

Click on any picture to check them out for yourself. Your students will love any of them.

What games do your students like to play?

Chat soon,

Evidence Based Practices and the Big 5

Evidence-based practices in education are the same. They are backed by rigorous, high-standard research, replicated with positive outcomes, and backed by their effects on student outcomes. EBPs take the guesswork out of teaching by providing specific approaches and programs that improve student performance. There is frustration in teaching when you cannot find a way to help your student learn. You try one thing and then another and another and they are not having positive outcomes for your student. EBPs have proven outcomes on students’ performance and can make finding and implementing an effective practice less frustrating.

Using evidence-based practices (EBPs), with special education students especially, is a critical feature of improving their learning outcomes. When teachers combine their expertise as content knowledge experts with explicit instruction and practices and programs backed by research, the likelihood that a child will grow academically is increased.

A quick history lesson

We all love or hate the Big 5.

BUT..... without them

Congress appointed a National Reading Panel (NPR) in 1997 to review reading research and determine the most effective methods for teaching reading. The NRP reviewed over 100,000 studies and analyzed them to see what techniques actually worked in teaching children to read. The group only looked at quantitative studies, which gathered data in a numerical form and through structured techniques. Qualitative studies, which gather data through observations such as interviews were not included. In 2000 the NRP submitted their final report. The results became the basis of the federal literacy policy at that time, which included “No Child Left Behind.” We still base our understanding of evidence-based reading research on the NPR, but sadly, some of their major recommendations have been largely ignored. So what were their findings? They concluded that there were five essential components to reading, known as “The Big Five:”

- Explicit instruction in Phonemic Awareness.

- Systematic Phonics Instruction.

- Techniques to improve Fluency. These include guided oral reading practices where the student reads aloud and the teacher makes corrections when the student mispronounces a word. A teacher can also model fluent reading to the student. Fluency includes accuracy, speed, understanding, and prosody. Word calling is not the same as fluency.

- Teaching vocabulary words or Vocabulary Development.

- Reading Comprehension.

On top of this comes systematic Phonics. Children learn that the sounds in spoken words relate to the patterns of letters in written words. Not just mastery of the skills of systematic phonics, but automaticity in those skills, is also necessary for fluency to develop.

With these two layers in place and developed to the point of automaticity, techniques to improve Fluency can begin to be effective.

Vocabulary Development can be built next, including learning the meaning of new words through direct and indirect instruction, and developing tools like morphemic analysis, to discover the meaning of an unknown word.

Then Comprehension Skills can be added. Comprehension skills are the strategies a reader can use to better comprehend a text.

This is the foundation of reading, but it is also the foundation of education generally. Every subject is dependent on reading, and mastery of these subjects depends on developing a strong foundation in these early literacy skills.

As I continue to explore Evidenced-Based Practices, I will use the “Big 5” to share how they can be developed, and provide some resources that you can take back and use.

Chat Soon,

Have to Teach Phonics? How???

What order should phonics be taught?

What about my students who struggle with reading? What can I do?

About Me

Resource Library

Thank you! You have successfully subscribed to our newsletter.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)