How Special Education Teachers Can Support the RTI/MTSS Process and Student Identification

As a special education teacher, one of the most impactful roles I’ve come to embrace is supporting the system that identifies and helps struggling learners—not just providing direct instruction. Frameworks like Response to Intervention (RTI) and Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) are designed to ensure students receive early, equitable support, and to help schools distinguish between students with disabilities and those who simply need better instruction or intervention. Done right, these systems reduce bias, promote data-driven decisions, and lead to accurate special education identification. to do it right, we must also understand what the law requires—and how special educators can support both the spirit and letter of those laws.

But to do it right, we must also understand what the law requires—and how special educators can support both the spirit and letter of those laws.

Understanding RTI and MTSS Through a Legal Lens

RTI is a prevention-oriented framework that provides increasingly intensive levels of instructional support. It’s most commonly used in identifying students with specific learning disabilities (SLD). According to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 2004), states may use a “process that determines if the child responds to scientific, research-based intervention” as part of an SLD evaluation (34 CFR §300.307(a)(2)).

MTSS is a broader framework that includes not only academic intervention but also behavioral and social-emotional supports. It incorporates RTI but emphasizes a whole-child approach. While not explicitly mentioned in federal special education law, MTSS is supported by multiple federal initiatives, including the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which encourages the use of evidence-based, multi-tiered systems to improve outcomes for all learners.

Special Education Teachers: Our Legal and Instructional Role in RTI/MTSS

1. Ensuring Fidelity of Interventions

Under IDEA, evaluations must be based on valid data (34 CFR §300.304). That’s only possible when interventions are implemented with fidelity. Special educators can:

- Model evidence-based strategies

- Observe and coach general education staff

- Help ensure interventions follow duration, frequency, and instructional protocols

When interventions are inconsistent or poorly implemented, we risk collecting invalid data—leading to misidentification or delayed services.

2. Collaborating on Progress Monitoring

IDEA requires that eligibility decisions draw from “a variety of sources,” including “technically sound instruments that may assess the relative contribution of cognitive and behavioral factors” (34 CFR §300.304(b)). That’s where progress monitoring comes in.

Special education teachers can:

Help select reliable tools aligned with academic or behavioral goals

Train staff in their use:

- Support data collection and analysis

- Join problem-solving teams to interpret whether lack of progress signals a potential disability

- Well-maintained data helps distinguish between a student who is underperforming and one who has a learning disability—and helps teams make timely, legally sound decisions.

3. Preventing Bias and Over-Referral

IDEA explicitly prohibits discrimination in evaluations: assessments must not be “discriminatory on a racial or cultural basis” and must be administered in the child’s native language or other mode of communication (34 CFR §300.304(c)(1)).

As special educators, we:

- Guide teams to examine instruction, attendance, behavior, and English language proficiency before referral

- Advocate for culturally responsive interventions

- Help ensure that referrals are based on need—not implicit bias, language differences, or socioeconomic factors

RTI/MTSS frameworks were developed in part to address the historical over-identification of students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. That mission continues today—and we have a responsibility to honor it.

Supporting the Evaluation and Identification Process

When students don’t respond to Tier 3 interventions, and there’s documented evidence of ongoing difficulties, a special education evaluation may be warranted. At that point, IDEA regulations guide our work:

Evaluations must be comprehensive and assess all areas of suspected disability (34 CFR §300.304(c)(4))

Teams must use a variety of assessment tools and strategies—not a single test or score (34 CFR §300.304(b))

Evaluation procedures must be non-discriminatory, administered by trained personnel, and used for their intended purposes

Special education teachers:

- Collaborate with school psychologists, speech therapists, and other professionals during evaluation

- Interpret RTI/MTSS data as part of the eligibility decision

- Ensure all pre-referral documentation is complete and consistent

- Keep timelines, parental consent, and procedural safeguards on track

- We are also often the bridge between school and family—making sure parents understand the process and their rights, and ensuring their voice is heard.

Know Your State Laws and Policies

While IDEA sets the federal standard, each state adds its own guidelines for using RTI/MTSS in the evaluation process. For example:

Illinois requires an RTI process be part of identifying a specific learning disability (ISBE, 23 Illinois Admin. Code 226.130).

California allows school districts to choose between RTI, the discrepancy model, or a combination (California Education Code §56337).

As educators, we must stay informed about our state's expectations so we can advocate for students while ensuring compliance.

RTI vs. Discrepancy Model Under IDEA (2004)

IDEA 2004 allows (but does not mandate) RTI as a method for identifying students with learning disabilities.

According to 20 U.S.C. § 1414(b)(6)(B):

“In determining whether a child has a specific learning disability, a local educational agency shall not be required to take into consideration whether a child has a severe discrepancy between achievement and intellectual ability...”

This means:

- Schools are no longer required to use the IQ-achievement discrepancy model.

- Schools are permitted to use a process based on the child’s response to scientific, research-based intervention (RTI).

- States can allow or require RTI, or offer flexibility for schools/districts to choose.

What Is the Discrepancy Model?

Historically, the discrepancy model identified a learning disability based on a gap between a student’s IQ and their academic performance. Critics argue it often delays intervention until a student is significantly behind—also known as the “wait to fail” model.

Walking the Line: Early Help vs. Over-Identification

RTI and MTSS aim to strike a balance: provide early help, but don’t over-identify. Special education teachers walk that tightrope daily.

Sometimes students are referred for evaluation too quickly—before interventions have been tried with fidelity. Other times, students with clear signs of disability are kept in Tier 2 or Tier 3 too long, delaying appropriate support.

Our expertise in both disabilities and instruction allows us to ask the right questions:

- Has the student received appropriate, research-based instruction?

- Are the interventions matched to the student’s specific needs?

- Are cultural, linguistic, and environmental factors being considered?

When we ask these questions and follow the data, we can ensure that students aren’t overlooked—or over-identified.

RTI and MTSS are more than educational frameworks—they’re part of a legal and ethical system that ensures all students get the support they need. And yes a general education process BUT special education teachers are essential to that system.

By supporting the fidelity of interventions, guiding data collection, preventing bias, and leading the evaluation process, we help schools fulfill their obligations under IDEA and ESSA—and, more importantly, we help students get what they need to thrive.

Chat Soon-

Additional reading on RTI and MTSS:

- Understanding Tier 2 in the Integrated Multi-Tiered System of Supports (iMTSS)

- Understanding Tier 1 Instruction: The Foundation of Effective Teaching

- Understanding Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) and Response to Intervention (RTI)

- Why a Comprehensive Special Education Evaluation?

- 101: MTSS & RTI

- Tier 2 Interventions: Take RTI to the Next Level

- MTSS What???

- What is RtI?

- What Parents needs to know about RTI

- RTI: Part 2

- RTI 101: Frequently Asked Questions (Part 1)

- RTI for Parents

Supporting Multilingual Learners with the Science of Reading: A Guide for General and Special Education Teachers

As educators, we know that learning to read is a complex process—and for students learning English as a second or additional language (often called Multilingual Learners or MLs), it can feel even more daunting. But the good news is that the Science of Reading (SoR), with its emphasis on evidence-based reading instruction, provides powerful tools to support all students, including those acquiring English.

However, using SoR approaches with MLs isn’t always straightforward. Let’s dig into the positives, the potential pitfalls, and most importantly, the strategies we can use to make reading instruction equitable, inclusive, and effective for all learners.

The Science of Reading: A Quick Overview

How SoR Helps Multilingual Learners

Where the Challenges Lie

- Assuming Language Deficit Instead of Language Difference

- MLs are not “behind” because they’re learning English—they are developing a second language. We must avoid confusing language acquisition with a learning disability (Harry & Klingner, 2006).

Overlooking Oral Language Development

Insufficient Comprehension Support

What We Can Do: Practical Strategies

Collaboration Between General and Special Education

PS: Make sure to grab 2 different freebies to help you in your journey to support ML learners. Click on the image below.

Citations:

- Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education.

- Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice.

- Harry, B., & Klingner, J. (2006). Why are so many minority students in special education? Teachers College Press.

- Sullivan, A. L. (2011). Disproportionality in special education identification and placement of English language learners. Exceptional Children.

Understanding Tier 2 in the Integrated Multi-Tiered System of Supports (iMTSS)

The Importance of Tier 2

1. Early Identification and Intervention: One of the primary goals of Tier 2 is to identify and support students who are at risk for academic difficulties early on. Research shows that early intervention is crucial for preventing long-term academic struggles. According to the National Reading Panel (2000), early reading interventions are significantly more effective than later remediation. By providing targeted support at the first sign of difficulty, educators can help prevent small issues from becoming significant obstacles.

2. Preventing the Matthew Effect: The Matthew Effect, coined by Stanovich (1986), refers to the phenomenon where "the rich get richer and the poor get poorer" in terms of reading skills. Students who start with strong reading skills tend to improve at a faster rate, while those with weak skills fall further behind. Tier 2 interventions are designed to prevent this effect by giving struggling readers the support they need to catch up with their peers.

3. Efficient Use of Resources: Tier 2 allows for a more efficient use of educational resources. By providing targeted interventions to small groups of students, schools can address learning gaps without overburdening the system. This targeted approach ensures that students receive the help they need without requiring the more intensive and resource-heavy supports of Tier 3.

What Tier 2 Is Not

Tier 2 is not simply reteaching Tier 1 instruction in the same way or increasing the time a student spends on general curriculum without adjusting how it’s delivered. According to Fuchs, Fuchs, and Compton (2012), effective Tier 2 instruction must be more explicit, more systematic, and more intensive than what students receive in the general education setting. It’s not a “wait and see” model where students are passively monitored—nor is it one-size-fits-all instruction. A student who struggles in Tier 1 needs targeted intervention that directly addresses their unique learning gaps, not just extra exposure to the same material that didn’t work the first time.

Additionally, Tier 2 is not special education or an automatic path to an Individualized Education Program (IEP). The purpose of Tier 2 is to prevent the need for more intensive services by addressing difficulties early and efficiently. IDEA 2004 encourages schools to use scientifically based interventions and progress monitoring as part of the evaluation process, but Tier 2 should never delay a referral to special education when appropriate. Tier 2 must be timely, data-driven, and carefully implemented to be effective—and should not be mistaken for a permanent placement or used as a gatekeeper for accessing special education services.

How Tier 2 Ties into the Science of Reading Best Practices

The science of reading is a body of research that encompasses what is known about how people learn to read. This research has led to evidence-based practices that are effective in teaching reading. Tier 2 interventions, when aligned with these best practices, can significantly enhance reading outcomes for students.

1. Explicit and Systematic Instruction: The science of reading emphasizes the importance of explicit and systematic instruction in foundational reading skills, such as phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Tier 2 interventions often focus on these areas, providing students with clear, direct teaching and practice opportunities.

Research Support: A study by Foorman et al. (2016) found that explicit instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics leads to significant improvements in reading outcomes for struggling readers.

2. Data-Driven Decision Making: Effective Tier 2 interventions rely on ongoing assessment and data analysis to identify students' needs, monitor progress, and adjust instruction as necessary. This data-driven approach ensures that interventions are tailored to each student's specific strengths and weaknesses.

Research Support: The use of curriculum-based measurement (CBM) has been shown to be effective in monitoring student progress and guiding instruction. Fuchs and Fuchs (2006) highlighted the importance of frequent progress monitoring in ensuring the success of interventions.

3. Small Group Instruction: Tier 2 interventions typically involve small group instruction, which allows for more personalized and intensive support. Small groups enable teachers to provide more immediate feedback and to differentiate instruction based on individual student needs.

Research Support: Wanzek and Vaughn (2007) found that small group reading interventions are more effective than whole-class instruction for students with reading difficulties, particularly when the groups are kept to a manageable size.

4. Multisensory Approaches: The science of reading supports the use of multisensory approaches, which engage multiple senses to reinforce learning. This can include visual, auditory, and kinesthetic-tactile activities that help students connect sounds to letters and words.

Research Support: Multisensory teaching methods, such as those used in the Orton-Gillingham approach, have been shown to be effective for students with dyslexia and other reading difficulties (Ritchey & Goeke, 2006).

Implementing Tier 2 Interventions

Effective implementation of Tier 2 interventions requires careful planning and ongoing evaluation. Here are some key steps:

1. Screening and Identification: Universal screening is essential for identifying students who may need Tier 2 support. Screening tools should be reliable and valid, and they should be administered regularly to catch issues early.

2. Designing Interventions: Interventions should be evidence-based and tailored to address the specific needs identified through screening and assessment. They should include explicit, systematic instruction in foundational reading skills and incorporate multisensory teaching methods where appropriate.

3. Progress Monitoring: Regular progress monitoring is crucial for assessing the effectiveness of interventions and making necessary adjustments. This involves frequent, brief assessments that provide data on student progress and inform instructional decisions.

4. Professional Development: Teachers need ongoing professional development to stay current with the latest research and best practices in reading instruction. This training should include strategies for delivering Tier 2 interventions and using data to guide instruction.

5. Family Involvement: Engaging families in the intervention process can enhance student outcomes. Parents and caregivers can support reading development at home through activities that reinforce skills being taught in school.

Challenges and Solutions

Implementing Tier 2 interventions can present challenges, but with thoughtful planning and collaboration, these can be overcome.

1. Resource Limitations: Schools may face limitations in staffing, time, and materials for Tier 2 interventions. Solutions include leveraging existing resources, such as paraprofessionals and volunteers, and seeking grants or other funding opportunities.

2. Fidelity of Implementation: Ensuring that interventions are implemented with fidelity is critical for their success. This requires ongoing training, supervision, and support for teachers, as well as regular observation and feedback.

3. Balancing Interventions with Core Instruction: It's important to ensure that Tier 2 interventions supplement, rather than replace, core instruction. This requires careful scheduling and coordination to ensure that students do not miss out on essential classroom learning.

Tier 2 interventions are a vital component of the iMTSS framework, providing targeted support to students who are at risk for academic difficulties. By aligning these interventions with the science of reading best practices—such as explicit and systematic instruction, data-driven decision making, small group instruction, and multisensory approaches—schools can significantly improve reading outcomes for struggling readers. Ongoing assessment, professional development, and family involvement are essential for the successful implementation of Tier 2 interventions. With the right support in place, all students can achieve reading success and reach their full potential.

Chat Soon-

References

- Fuchs, L. S., & Fuchs, D. (2006). Introduction to response to intervention: What, why, and how valid is it? Reading Research Quarterly, 41(1), 93-99.

- Foorman, B. R., Francis, D. J., Fletcher, J. M., Schatschneider, C., & Mehta, P. (1998). The role of instruction in learning to read: Preventing reading failure in at-risk children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(1), 37-55.

- National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

- Ritchey, K. D., & Goeke, J. L. (2006). Orton-Gillingham and Orton-Gillingham–based reading instruction: A review of the literature. The Journal of Special Education, 40(3), 171-183.

- Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21(4), 360-407.

- Wanzek, J., & Vaughn, S. (2007). Research-based implications from extensive early reading interventions. School Psychology Review, 36(4), 541-561.

Understanding Tier 1 Instruction: The Foundation of Effective Teaching

This is the bottom of the pyramid because it means ALL means ALL. All the students in your class are receiving a guaranteed and viable curriculum that is being provided explicitly and following a scope and sequence.

Students are general education students first.

If you have more than 50% of your students needing interventions. You have a core instruction or Tier 1 problem. NOT AN INTERVENTION PROBLEM.

In the landscape of what our classrooms look like it's getting harder to ensure that all students receive high-quality instruction is a primary goal. At the heart of this mission lies Tier 1 instruction, also known as core instruction. This foundational level of teaching is critical for meeting the diverse needs of students in the classroom and ensuring that all students, regardless of their background or abilities, have access to a rigorous and engaging education.

What is Tier 1 Instruction?

Tier 1 instruction is the baseline level of teaching that all students receive in a general education classroom. It is designed to be effective for the majority of students, providing a strong foundation in key academic areas. The primary aim of Tier 1 instruction is to deliver high-quality, evidence-based teaching practices that promote student learning and achievement.

What are Diagnostic Assessments?

Diagnostic assessments in education are tools used to identify students' strengths, weaknesses, knowledge, and skills prior to instruction. They help educators understand students' learning needs and tailor instruction accordingly. Here are some key features and purposes of diagnostic assessments:

Identification of Learning Gaps: They identify specific areas where students are struggling or excelling, allowing for targeted interventions.

Personalized Instruction: The results can inform differentiated instruction strategies to meet the diverse needs of students.

Baseline Data: They provide baseline data to measure student growth over time.

Early Intervention: Early identification of learning difficulties enables timely support and intervention, preventing minor issues from becoming major obstacles.

Informed Instructional Planning: Teachers can use the data to plan lessons that address the specific needs of their students, enhancing the effectiveness of instruction.

Examples of diagnostic assessments include:

Pre-tests: Assessments given before a unit or course to gauge prior knowledge.

Screening Tests: Brief assessments to identify students at risk of academic difficulties.

Reading Inventories: Tools that assess reading skills, such as phonemic awareness, fluency, and comprehension.

Math Diagnostics: Assessments that evaluate specific math skills and concepts.

Diagnostic assessments are an essential component of the Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS), particularly in Tier 2, where they help identify students who need additional support and inform the development of targeted interventions.

Examples of Diagnostic Assessments are iReady and STARR.

What Universal Assessments?

Universal assessments in education are standardized tests administered to all students within a specific grade level, school, or district to evaluate their academic performance and identify areas needing improvement. These assessments are designed to provide a broad overview of students' skills and knowledge, ensuring that educators can make informed decisions about curriculum and instruction.

Here are some key aspects of universal assessments:

Screening: They serve as a screening tool to identify students who may need further diagnostic assessment or intervention.

Benchmarking: Universal assessments help establish performance benchmarks and track student progress over time.

Equity: They ensure that all students are assessed using the same criteria, promoting fairness and equity in education.

Accountability: Results from these assessments are often used for accountability purposes, informing policy decisions, and evaluating educational programs.

Data-Driven Decision Making: The data gathered helps educators and administrators make informed decisions about resource allocation, instructional strategies, and professional development needs.

Examples of universal assessments include:

State Standardized Tests: These are mandated by state education departments and cover subjects such as math, reading, and science.

National Assessments: Examples include the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in the United States.

Universal Screening Tools: Brief assessments administered to all students at the beginning of the school year to identify those at risk of academic difficulties. Examples include Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS) and Measures of Academic Progress (MAP).

Formative Assessments: Tools like quizzes or interim assessments that provide ongoing feedback to teachers and students.

Universal assessments are a critical component of the Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS), particularly in Tier 1, where they help ensure that all students receive high-quality, standards-aligned instruction and that those who need additional support are identified early.

The Importance of Tier 1 Instruction

Inclusivity and Equity: Tier 1 instruction ensures that every student has access to quality education. By implementing effective teaching strategies at this level, educators can address the diverse needs of their students, reducing the achievement gap and promoting equity in education.

Preventative Approach: High-quality Tier 1 instruction serves as a preventative measure, reducing the need for more intensive interventions. When core instruction is strong, fewer students will require additional support, which can be time-consuming and costly.

Efficiency in Resource Allocation: By focusing on improving Tier 1 instruction, schools can allocate their resources more efficiently. Effective core instruction reduces the strain on special education services and intervention programs, allowing those resources to be directed to students who need them the most.

Foundation for Lifelong Learning: Strong Tier 1 instruction lays the groundwork for lifelong learning. It equips students with essential skills and knowledge, fostering a love for learning and encouraging them to pursue further education and personal development.

Strategies in Implementing Science of Reading Best Practices in Core Instruction

To ensure that Tier 1 instruction aligns with the science of reading, teachers must integrate evidence or research based practices into their teaching. Here are some strategies to consider:

- Explicit Instruction: Explicit teaching involves clear, direct instruction on specific skills and concepts. This approach is particularly effective for teaching phonemic awareness and phonics. For example, teachers can use systematic phonics programs that guide students through a sequence of letter-sound relationships, starting with the simplest and gradually increasing in complexity.

- Systematic and Sequential Instruction: Reading instruction should follow a logical sequence, building on previously taught skills. This approach helps students develop a solid foundation and ensures that they master basic skills before moving on to more complex ones.

- Differentiated Instruction: While Tier 1 instruction is designed to meet the needs of most students, it is important to recognize that students have varying abilities and learning styles. Differentiated instruction involves tailoring teaching methods and materials to accommodate these differences. For example, teachers can use small group instruction to provide additional support to students who are struggling with specific skills.

- Integrated Literacy Activities: Reading instruction should be integrated with other areas of the curriculum, such as writing, speaking, and listening. This holistic approach reinforces literacy skills and helps students see the relevance of reading in different contexts.

- Ongoing Assessment and Feedback: Regular assessment and feedback are essential for monitoring student progress and adjusting instruction as needed. Formative assessments, such as running records and informal reading inventories, provide valuable insights into students’ reading abilities and help teachers identify areas where additional support is needed.

Strategies for Implementing Math Best Practices in Core Instruction

Implementing best practices in math instruction is essential for fostering a deep understanding of mathematical concepts among students. Effective math instruction not only helps students succeed academically but also equips them with critical thinking and problem-solving skills necessary for real-world applications. Here are several strategies classroom teachers can use to implement math best practices in their core instruction.

1. Focus on Conceptual Understanding: One of the most crucial aspects of effective math instruction is helping students develop a deep conceptual understanding of mathematical concepts. Instead of merely teaching procedures and algorithms, focus on the underlying principles. Use visual aids, manipulatives, and real-life examples to illustrate abstract concepts. Encourage students to explain their reasoning and explore different ways to solve problems. By building a strong foundation of conceptual knowledge, students are better equipped to tackle complex problems and apply their learning in various contexts.

2. Incorporate Problem-Solving and Critical Thinking: Mathematics is not just about finding the right answers; it's about understanding the process and thinking critically about problems. Incorporate problem-solving activities that challenge students to think creatively and reason logically. Present open-ended problems that have multiple solutions or approaches. Encourage students to discuss their problem-solving strategies with peers and justify their reasoning. This practice not only enhances their critical thinking skills but also promotes a growth mindset, where students view challenges as opportunities to learn and improve.

3. Use Formative Assessments: Formative assessments are essential tools for gauging student understanding and guiding instruction. Regularly use formative assessments such as quizzes, exit tickets, and informal observations to check for understanding. Analyze the results to identify areas where students are struggling and adjust your instruction accordingly. Formative assessments provide immediate feedback to both teachers and students, allowing for timely interventions and support.

4. Differentiate Instruction: In any classroom, students have diverse learning needs and paces. Differentiating instruction ensures that all students have access to the curriculum and can succeed. Use flexible grouping to provide targeted instruction based on students' needs. Offer varied tasks and activities that cater to different learning styles and levels of readiness. Incorporate technology and online resources to provide personalized learning experiences. Differentiation allows you to meet students where they are and help them progress effectively.

5. Promote Mathematical Discourse: Encouraging mathematical discourse in the classroom helps students articulate their thinking and deepen their understanding. Create a classroom environment where students feel comfortable sharing their ideas, asking questions, and engaging in discussions. Use open-ended questions and prompts to stimulate conversation. Encourage students to explain their reasoning, critique the reasoning of others, and build on each other's ideas. Mathematical discourse not only enhances understanding but also fosters a collaborative learning community.

6. Integrate Technology: Technology can be a powerful tool in math instruction when used effectively. Use digital tools and resources to enhance learning and engagement. Interactive math software, virtual manipulatives, and online games can provide dynamic and interactive experiences that make learning math fun and engaging. Additionally, technology can facilitate differentiated instruction by providing personalized learning paths and instant feedback.

7. Connect Math to Real-Life Contexts: Making math relevant to students' lives helps them see the value and application of what they are learning. Incorporate real-life contexts and problems into your lessons. Use examples from everyday life, such as shopping, cooking, or sports, to illustrate mathematical concepts. Engage students in projects that require them to apply their math skills to solve real-world problems. Connecting math to real-life situations makes learning more meaningful and motivates students to engage with the content.

8. Provide Ongoing Professional Development: Continual professional development is essential for staying current with best practices in math instruction. Participate in workshops, conferences, and professional learning communities to enhance your teaching skills and knowledge. Collaborate with colleagues to share strategies and resources. Reflect on your practice and seek feedback to improve your instruction. Ongoing professional development ensures that you are equipped with the latest research and techniques to provide high-quality math instruction.

Challenges and Considerations

Implementing high-quality Tier 1 instruction is not without its challenges. Here are a few considerations for educators:

1. Professional Development: Ensuring that teachers have the knowledge and skills to implement evidence-based reading practices requires ongoing professional development. Schools must invest in training programs that equip teachers with the latest research and instructional strategies.

2. Curriculum Alignment: The curriculum must align with the principles of the science of reading. Schools should evaluate their reading programs and materials to ensure they support systematic and explicit instruction.

3. Time and Resources: Effective reading instruction requires adequate time and resources. Schools must prioritize literacy instruction and allocate sufficient time for teachers to plan, teach, and assess student learning.

4. Student Engagement: Keeping students engaged and motivated is crucial for successful reading instruction. Teachers should use a variety of instructional strategies and materials to maintain student interest and encourage a love for reading.

Tier 1 instruction forms the bedrock of an equitable and effective grade level instruction, ensuring that all students receive a guaranteed and viable curriculum delivered through explicit teaching and a well-defined scope and sequence. Recognizing that general education students are the priority, a high percentage of students needing intervention signals a need to strengthen core instruction rather than solely focusing on interventions. Diagnostic and universal assessments play crucial roles in informing and monitoring the effectiveness of this foundational tier. Ultimately, prioritizing robust Tier 1 instruction fosters inclusivity, prevents the overuse of intervention resources, and builds a strong academic foundation for all learners.

Understanding Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) and Response to Intervention (RTI)

What is a Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS)?

MTSS is a comprehensive framework that aims to provide targeted support to students based on their individual needs. It integrates assessment and intervention within a multi-level prevention system to maximize student achievement and reduce behavioral problems. The MTSS framework typically consists of three tiers:

Tier 1: Universal Interventions

Description: This tier includes high-quality instruction and behavioral support for all students in the general education classroom. It is preventive and proactive.

Purpose: To ensure that all students receive effective core instruction that meets their diverse needs.

Tier 2: Targeted Interventions

Description: This tier provides additional support for students who are not making adequate progress with Tier 1 interventions. It often includes small group interventions.

Purpose: To address specific learning or behavioral needs that are not being met by universal interventions.

Tier 3: Intensive Interventions

Description: This tier involves individualized and intensive interventions for students who continue to struggle despite the support provided in Tiers 1 and 2.

Purpose: To offer highly personalized interventions for students with significant and persistent difficulties.

What is the Response to Intervention (RTI)?

RTI is a multi-tier approach to the early identification and support of students with learning and behavior needs. Like MTSS, RTI consists of three tiers, but it is more specifically focused on identifying and providing early interventions for students who are at risk for poor learning outcomes. The RTI process includes:

Universal Screening Includes:

- Description: All students are assessed to identify those at risk for poor learning outcomes.

- Purpose: To ensure early identification and support.

Progress Monitoring

- Description: Students' progress is regularly monitored to assess the effectiveness of interventions.

- Purpose: To make data-driven decisions about the intensity and duration of interventions.

Data-Based Decision-Making

- Description: Decisions about the intensity and duration of interventions are based on data collected from progress monitoring.

- Purpose: To ensure that interventions are effective and appropriately tailored to students' needs.

The Need for MTSS and RTI in Supporting All Students

Addressing Diverse Learning Needs

One of the primary reasons for the implementation of MTSS and RTI is the recognition that students come to school with a wide range of learning needs. These frameworks ensure that all students receive the level of support they need to succeed. According to the National Center on Intensive Intervention, MTSS and RTI help in "providing high-quality instruction and intervention matched to student need, monitoring progress frequently to make decisions about changes in instruction or goals, and applying child response data to important educational decisions."

Promoting Equity in Education

MTSS and RTI frameworks promote educational equity by ensuring that all students, regardless of their background or learning needs, have access to high-quality instruction and support. This approach is particularly important in addressing disparities in educational outcomes for historically underserved student groups. The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) emphasizes the importance of equity and accountability in education, aligning with the principles of MTSS and RTI.

Identifying Students with Learning Disabilities

Early Identification and Intervention

One of the critical roles of MTSS and RTI is the early identification of students with learning disabilities. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) mandates that schools identify and provide services to students with disabilities. MTSS and RTI frameworks facilitate this by providing a structured approach to identifying students who are struggling and providing them with targeted interventions.

Reducing the Over-Identification of Disabilities

Historically, there has been a concern about the over-identification of students, particularly minority students, for special education services. MTSS and RTI help address this issue by ensuring that students receive appropriate interventions before being referred for special education evaluation. This approach helps distinguish between students who have a learning disability and those who simply need additional support to meet grade-level expectations.

Research Supporting MTSS and RTI

Numerous studies highlight the effectiveness of MTSS and RTI in improving student outcomes. For example, a study published in the journal "School Psychology Review" found that schools implementing RTI with fidelity saw significant improvements in reading outcomes for students (Burns, Appleton, & Stehouwer, 2005). Additionally, a meta-analysis conducted by Fuchs and Fuchs (2006) demonstrated that RTI practices are effective in reducing the number of students identified with learning disabilities, while also improving overall academic performance.

Legal Foundations of MTSS and RTI

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

IDEA is the primary federal law governing special education services in the United States. It requires schools to provide a free appropriate public education (FAPE) to students with disabilities and emphasizes the importance of early intervention and progress monitoring, key components of MTSS and RTI.

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)

ESSA, which reauthorized the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), places a strong emphasis on accountability and the use of evidence-based interventions to improve student outcomes. ESSA supports the use of MTSS and RTI frameworks to ensure that all students receive the support they need to succeed academically and behaviorally.

Implementing MTSS and RTI in Schools

Professional Development

Effective implementation of MTSS and RTI requires ongoing professional development for educators. Teachers need to be trained in evidence-based instructional practices, progress monitoring techniques, and data-driven decision-making processes.

Collaborative Approach

Successful MTSS and RTI implementation relies on a collaborative approach involving educators, administrators, parents, and specialists. Collaboration ensures that interventions are coordinated and aligned with students' needs.

Data-Driven Decision Making

Central to MTSS and RTI is the use of data to inform instructional decisions. Schools must establish systems for collecting, analyzing, and using data to monitor student progress and adjust interventions as needed.

Challenges and Considerations

Resource Allocation

Implementing MTSS and RTI effectively requires adequate resources, including time, personnel, and materials. Schools must ensure that they have the necessary resources to support these frameworks.

Fidelity of Implementation

The success of MTSS and RTI depends on the fidelity of implementation. Schools must ensure that interventions are delivered as intended and that progress monitoring is conducted consistently and accurately.

MTSS and RTI are an essential framework for supporting the diverse needs of all students and for identifying students with learning disabilities. By providing a structured approach to intervention and progress monitoring, these frameworks help ensure that all students receive the support they need to succeed academically and behaviorally. The legal and research foundations underpinning MTSS and RTI highlight their importance in promoting equity and improving educational outcomes for all students. As schools continue to implement and refine these frameworks, ongoing professional development, collaboration, and data-driven decision-making will be crucial to their success.

If you are looking for additional posts on RTI & MTSS Click Here

Chat Soon-

The Ongoing Journey: Problem Solving in Special Education with iReady Insights

What is RIOT/ICEL and what does it have to do with my vocabulary project??

How it all works?

RIOT: (Review, Interview, Observation, Test)

ICEL–Instruction, Curriculum, Environment, and Learner

Why a Comprehensive Special Education Evaluation?

The Framework

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires that special education evaluations be sufficiently comprehensive to make eligibility decisions and identify the student’s educational needs, whether or not commonly linked to the disability category in which the student has been classified (34 CFR 300.304). Comprehensive evaluations are conducted in a culturally and linguistically responsive manner; non-discriminatory for students of all cultural, racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and other backgrounds. When conducting special education evaluations, IEP teams must follow all procedural and substantive evaluation requirements specified in IDEA.

The BIG Ideas

- Special education evaluations must be sufficiently comprehensive for IEP teams to determine special education eligibility or continuing eligibility and to identify the educational needs of the student, whether or not commonly linked to the student’s identified disability category(ies).

- A comprehensive evaluation is a process, not an event. IEP team participants work together to explore, problem-solve, and make decisions about eligibility for special education services. If found eligible, the IEP team uses information gathered during the evaluation to collectively develop the content of the student’s IEP.

- A comprehensive special education evaluation actively engages the family throughout the evaluation process.

- Comprehensive evaluations are first and foremost “needs focused” on identifying academic and functional skill areas affected by the student’s disability, rather than “label focused” on identifying a disability category label which may or may not, accurately infer student need.

- Developmentally and educationally relevant questions about instruction, curriculum, environment, as well as the student, guide the evaluation. Such questions are especially helpful during the review of existing data to determine what if any, additional information is needed.

- Asking clarifying questions throughout the evaluation helps the team explore educational concerns as well as student strengths and needs such as barriers to and conditions that support student learning, and important skills the student needs to develop or improve.

- Culturally responsive problem-solving and data-based decision-making using current, valid, and reliable (i.e. accurate) assessment data and information is critical to conducting a comprehensive evaluation.

- Assessment tools and strategies used to collect additional information must be linguistically and culturally sensitive and must provide accurate and useful data about the student’s academic, developmental, and functional skills.

- Data and other information used during the evaluation process is collected through multiple means including review, interview, observation, and testing; as well as across domains of learning including instruction, curriculum, environment, and learner.

- Individuals who collect and interpret assessment data and other information during an evaluation must be appropriately skilled in test administration and other data collection methods. This includes understanding how systemic, racial, and other types of bias may influence data collection and interpretation, and how individual student characteristics may influence results.

- Assessment data and other information gathered over time and across environments help the team understand and make evaluation decisions about the nature and effects of a student’s disability on their education.

- Comprehensive evaluations must provide information relevant to making decisions about how to educate the student. A comprehensive evaluation provides the foundation for developing an IEP that promotes student access, engagement, and progress in age or grade-level general education curriculum, instruction, and other activities, and environments.

The Balcony View

Comprehensive evaluations must provide information relevant to making decisions about how to educate the student so they can access, engage, and make meaningful progress toward meeting age and grade level standards. Assessment and collection of additional information play a central role during the evaluation and subsequently in IEP development and reviewing student progress.

A comprehensive evaluation takes into account Career Readiness, a growing awareness of the relationship between evaluation and IEP development, and the need for information about how special education evaluations and reevaluations can be made more useful for IEP development.

The 2017 US Supreme Court Endrew F. case also brought renewed attention to the importance of knowing whether a student's IEP is sufficient to enable a student with a disability to make progress “appropriate in light of their circumstances.” Finally, updated guidance, including results of statewide procedural compliance self-assessment, IDEA complaints addressing whether evaluations are sufficiently comprehensive, and continuing disproportionate disability identification, placement, and discipline in student groups who traditionally are not equitably served.

A comprehensive evaluation responds to stakeholders’ requests for more information and reinforces that every public school student graduates ready for further education, the workplace, and the community.

It seeks to ensure a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) for every student protected under IDEA. It guides IEP teams in planning and conducting special education evaluations that explicitly address state and federal requirements to conduct comprehensive evaluations that help IEP teams to determine eligibility, and thoroughly and clearly identify student needs.

Planning and Conducting a Comprehensive Special Education Evaluation

An Individualized Education Program (IEP) is the key to addressing a student’s disability-related needs.It describes annual goals and the supports and services a student must receive so they can access, engage, and make progress in general education.

A well-developed IEP is a vehicle to ensure that a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) is provided to students protected under IDEA. A comprehensive special education evaluation provides the foundation for effective IEP development.

A comprehensive special education evaluation is conducted by a student’s IEP team appointed by the district. The IEP team must include the parent as a required participant and essential partner in decision-making. Special Education evaluation is a collaborative IEP team responsibility. During the evaluation process, the team collectively gathers relevant information and uses it to make accurate and individualized decisions about a student’s eligibility or continuing eligibility, effects of disability, areas of strength, and academic and functional needs.

Data and other information used to make evaluation decisions come from a variety of sources and environments, often extending beyond the IEP team. Guided by educationally relevant questions, both existing and new information is compiled or collected, analyzed, integrated, and summarized by the IEP team to provide a comprehensive picture of the student’s educational strengths and needs.

A comprehensive special education evaluation is grounded in a culturally responsive problem-solving model in which potential systemic, racial, and other bias is addressed, and hypotheses about the nature and extent of the student’s disability are generated and explored.

Conducting a comprehensive special education evaluation requires planning. Each team has its own methods for planning and conducting comprehensive special education evaluations with guidance from the state and district.

Why RIOT/ICEL Matrix?

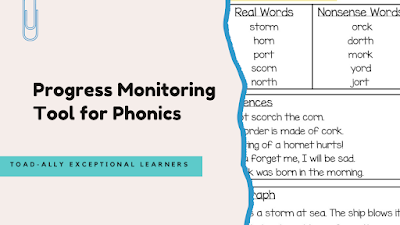

Feeling unsure about a student's phonics level? This new resource will instantly help

Have you ever sat in a meeting reviewing phonics data and someone asks if the student has mastered reading digraphs because the student doesn't demonstrate this in their small group?

Whether in an RTI meeting or just reviewing the data, this information helps plan the student's specific next steps.

If your phonics program is like mine--it didn't come with a quick way to progress monitor a student after you have taught a sound (phonogram). And sometimes you need more than dictation and how they read in the last decodable text.

You need more than a gut check BUT you need a number to prove what the student knows.

This Progress Monitoring Tools for Phonics solves this problem. It's quick and super easy to give after you have taught a sound. You can learn if students can read the phonogram at the word level (real & nonsense), sentence level, or in a paragraph with controlled text.

I use this Phonics Tool as a pre/post with mixed sounds. This has a very specific set of sounds such as all short, all R-controlled or all digraphs. Then I can teach the sounds in the pattern, reassess and have the data to prove if they have it or not.

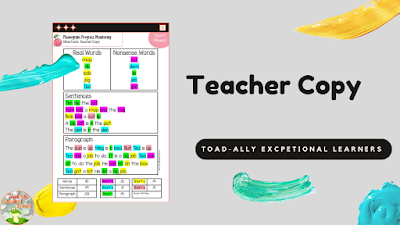

The teacher's copy of the tool is colored-coded to make it super easy to score and make decisions about what to do next. This progress monitoring tool can be completed by teachers, para-professionals, or volunteers.

Each phonogram has its own page and you can find it again on a mixed pattern page. I have made the Phonics Progress Monitoring Tool paperless as well. It can be used with Google. The link is within the product.These sheets can be completed are perfect for small targeted groups and are a perfect addition to any Orton-Gillingham Practice or Phonics Intervention.

You can expect updates throughout the year including Vowel teams, Suffixes, -ng & -nk, and more!!

Grab your today before the price increases!

Chat Soon,

About Me

Resource Library

Thank you! You have successfully subscribed to our newsletter.