POW: Readers Needing More Support--Adapted Books with High Frequency Words

How do I get my readers more exposure to high-frequency or Red Words???

ADAPTED BOOKS

I love adapted books. My students LOVE them too! They are one of my favorite tools in my classroom. When it comes to building language skills or more experience with text--adapted books are a great way to effectively target specific skills in a way that is engaging for students.

What is an Adapted Book?

Adapted books are books that have been modified in some way and often make it easier for students with disabilities to use but I also find adapted books are more engaging for all students to read and target so many critical language skills. I create and use adapted books all the time because they are interactive, motivating, and target various language skills. Many allow the students to feel successful and part of the book because they have to add or move pieces within the book.

Why You Need Adapted Books?

Research tells us kids with severe and profound disabilities often get sub-par literacy instruction. Part of that is based on people’s assumptions about the abilities of students with complex disabilities, the idea that instructional materials should only focus on functional or sight word instruction, and fact that language skills are generally lacking for students in this population. The other part of that is a feeling that instructional materials are just not made for these students in a way that is accessible.

There are a couple of big targets you are trying to hit when you add adapted books or novels to your classroom and lessons. One of them is to increase a student’s access to literature. You would be amazed at how many classrooms have NO appropriate reading materials in their classrooms. Because our students take longer to learn new skills, available literature tends to be juvenile or fully functional.

It is imperative students with severe disabilities are exposed to developed ideas and advanced concepts as a means of improving overall literacy and adapted books are the perfect vehicle to do that.

Adapted books can vary in skill level and be used for a wide variety of students with different skill sets and literacy skills. Many times there are pictures associated with the vocabulary terms so it provides those extra visual supports to help with understanding and comprehension of the verbal message. As the books become more challenging students rely less on pictures and more on written words.

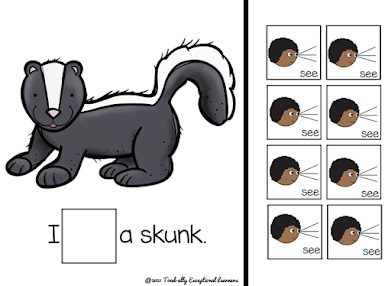

What is a High-Frequency Adapted Book?

Predictable texts are a specific type of book used in the earliest stages of reading instruction. It provides students with more frequent exposure to the targeted word. The texts have a repeated sentence or phrase on each page, typically with one variable word. A picture accompanies each sentence that allows the student to guess the variable word using the picture.

Errorless teaching is an instructional strategy that ensures children always respond correctly. Each page has only one answer--the target word. This means students are getting more frequent correct exposure to the word than reading authentic text where they can guess at the word.

Why Have Visuals Tied to Text?

Visuals are consistent. Visuals allow time for language processing. Visual prompts can offer a visual image and written word to meet the needs of a variety of students’ abilities. Visuals help students see what a word means. Visuals help to build independence.

So What Should I Do?

The first thing you should do is get this FREE adapted book by clicking here! Yeah. I love my readers… a lot. This is a very simple book.

Are you wanting more???? This bundle has 7 more to help you build your student's high-frequency reading knowledge.

Chat Soon-

PS--Bundle 2 coming soon

3 Fan Favoriate Phonemic Awareness Ideas (that are free)

What is Phonemic Awareness?

Phonemic Awareness (PA) is:

- the ability to hear and manipulate the sounds in spoken words and the understanding that spoken words and syllables are made up of sequences of speech sounds

- essential to learning to read in an alphabetic writing system, because letters represent sounds or phonemes. Without phonemic awareness, phonics makes little sense

- fundamental to mapping speech to print. If a child cannot hear that "man" and "moon" begin with the same sound or cannot blend the sounds /rrrrrruuuuuunnnnn/ into the word "run", he or she may have great difficulty connecting sounds with their written symbols or blending sounds to make a word

- essential to learning to read in an alphabetic writing system

- a strong predictor of children who experience early reading success

Why is it important?

- It requires readers to notice how letters represent sounds. It primes readers for print

- It gives readers a way to approach sounding out and reading new words

- It helps readers understand the alphabetic principle (that the letters in words are systematically represented by sounds)

...but difficult:

- Although there are 26 letters in the English language, there are approximately 40 phonemes, or sound units, in the English language

- Sounds are represented in 250 different spellings (e.g., /f/ as in ph, f, gh, ff)

- The sound units (phonemes) are not inherently obvious and must be taught. The sounds that make up words are "coarticulated;" that is, they are not distinctly separate from each other

What Does the Lack of Phonemic Awareness Look Like?

Children lacking phonemic awareness skills cannot:

- group words with similar and dissimilar sounds (mat, mug, sun)

- blend and split syllables (f oot)

- blend sounds into words (m_a_n)

- segment a word as a sequence of sounds (e.g., fish is made up of three phonemes, /f/ , /i/, /sh/)

- detect and manipulate sounds within words (change r in run to s)

How I Increased Reading Fluency Scores

She is a second-grade student who has struggled with her self-confidence when reading and just learning how to read for the last year.

She represents the students I teach reading to every day.

- No self-confidence

- Beginning reader

- No strategies

- No sight word knowledge

Oh, but unlike others, they have increased their sight word knowledge by 50% in 15 weeks. They have self-confidence and strategies when approaching an unknown text. And classroom teachers, are seeing these changes when they are in guided reading.

How did I do this?

Most of the students I see during my day are beginning readers. Technically this means students reading Levels A-E. For students to read the book more than twice and NOT have the whole thing memorized, is a whole different problem. (If you have looked, just like I have, then you know it doesn’t exist.)

Passage Reading with Sight Words to the RESCUE

These passages pick up where guided reading leaves off. My students love the fact they can read 90% of the words so they can focus on their reading fluency.

Each passage starts with a one-minute cold read. Students graph their score.

When you come back the next day, I help them practice the passage as many times they want before timing it again.

Students keep the same passage until reaching mastery. [Chick here to get yours.]

REASONS WHY IT WORKS

It works because students are placed in reading passages at their independent reading level. This means they are not struggling with every word like they would in most reading fluency passages.

I have written about Repeated Readings in the past as I create interventions--using John Hattie. My students love them and see each reading as a challenge to beat their score from the previous day. Tieing repeated reading with students doing their own data tracking has doubled their sight word scores and their grade level reading fluency scores.

I have written about Repeated Readings in the past as I create interventions--using John Hattie. My students love them and see each reading as a challenge to beat their score from the previous day. Tieing repeated reading with students doing their own data tracking has doubled their sight word scores and their grade level reading fluency scores.Student’s get tripped up on the sight words and can practice them without having to worry about the remaining text.

The Sight Word Cards are a way to quickly practice 5, 10, or 20 sight words. Each card is just for five days. [grab your here]

Max does his card as soon as he comes in. He started with reviews his personalized sight word deck of 10 cards and then moves right into his Sight Word Fluency Card.

He has struggled with learning his sight words since first grade. He never thought he would learn to read; let alone learn to love it!

I love that students graph their own data. This creates ownership and by-in. It builds self-confidence. It builds a love of reading.

I do all this fluency practice at the end of my lessons because it only takes 10 minutes. In those 10 minutes, I get daily progress monitoring of IEP goals, plan reading instruction, and build fluency.

By providing students with daily sight word fluency practice where students track their own data so that their instructional reading levels increase. Hattie's data adds evidence to what has become my go-to addition to their core intervention program.

In my district carry over back to grade level curriculum is HUGE! If it doesn't close gaps or classroom teacher don't see progress--you can forget about holding the course.

For those last ten minutes of group I spend focusing on reading fluency and sight words, I have seen a growth in sight words, self-confidence to attack more difficult text, and growth on grade level reading assessments.

My Classroom teachers are reporting student spending less time in their guided reading text because students are demonstrating solid decoding accuracy that has improved reading comprehension.

Chat Soon,

How to Create an RTI Intervention

I started looking at the triangle tier diagram wondering if I could improve on it only to discover that if you’ve seen one triangle diagram, you’ve seen one triangle diagram. There are a lot of differences from one to the other. Some show that tier 3 is special education services, some show that special ed is the next step after the triangle. Some indicate that tier 1 includes all students. The RTI Network says that tier 1 is low-level interventions in the classroom that not all students would need. They state that when these tier 1 interventions are successful, students are “returned to the regular classroom program.” So that would mean that students who never need interventions are actually not a part of tier 1.

I started looking at the triangle tier diagram wondering if I could improve on it only to discover that if you’ve seen one triangle diagram, you’ve seen one triangle diagram. There are a lot of differences from one to the other. Some show that tier 3 is special education services, some show that special ed is the next step after the triangle. Some indicate that tier 1 includes all students. The RTI Network says that tier 1 is low-level interventions in the classroom that not all students would need. They state that when these tier 1 interventions are successful, students are “returned to the regular classroom program.” So that would mean that students who never need interventions are actually not a part of tier 1.Here’s what I concluded: each school/district is going to choose what RTI means to them and how it is implemented in their jurisdiction. One thing stays the same: teachers need a way to document interventions and create interventions regardless of how their schools define tiers. For example in my building special education is not on the pyramid and the only tier 3 support my building currently has is Reading Recovery for K-1. Classroom teachers have to create all interventions using what they have access to in their classrooms. This is the first year where I have been in a position to provide direct tier 2 support. (Even as a special education teacher, I do not have access to tier 3 interventions.)

My job this year is to help classroom teachers create successful, purposeful, data drive interventions that lead students either through the special education identification process or help them go

back to core instruction.

Big Picture

I help teachers take these data, guide them in creating an intervention, create a SMART goal, and determine how they will collect the data. I love this. It works no matter the size of the group. Here's a snapshot of how I do that.

For this example, if these guys are identified with learning disabilities and also receive tier 2 interventions from the classroom teacher in addition to the core reading instructions she provides.

As a result, the classroom teacher has a smart goal (Read plan & SLO). I have also created a smart goal for this group.

Goal #1: When given daily small group reading, Polar Bears will increase their guided reading level from 3/C to F/10 by March 1.

Goal #2: When given daily small group targeted reading, Polar Bears will decrease the number of errors on a DRA 4/C from 51% accuracy to 90% on running records by January 31 to demonstrate independence on a DRA 4.

The second goal was added once we saw they were not reading what was written in the book and felt they needed a separate goal to work on this particular skill with me in a group but this was layered with the 1st.

From their data, which we used their mid-year DRAs to set the baseline for the intervention. Then the SMART goal. So what did this intervention look like? We talked about not changing anything in their guided reading as we could see they weren't reading what was written, we theorized adding a reward for reading correctly was going to be our first stop. Hence, the short time frame for the goal.

The Plan: keep doing targeted guided reading in Level DRA 4s and add a reward for reading each word correctly. The other change--keep the same book for the week to really focus on decoding first and spend the last day on comprehension.

The Problem: Progress monitoring. The DRA was going to be the pre and post-intervention data. They needed to be Independent 4 in a month. I decided to pre/post each guided reading book. To not take group time on Tuesday, I’d pull them Monday for a cold read to create the pretest data. The post running record would be Friday. 4 days to work the text.

The Reward: My school psychologist always suggests using something that is highly motivating for the student. (I used beads to keep track of words read correctly.) With both of the boys: 1 word---candy. Yes, candy. (I know!) To help not let them walk off with 100 pieces apiece; I set up an exchange. I would also change that exchange each day as they got better. For example: first read--15 correct words equals 1 piece. Second read--20 pieces equals 1 piece. And so on. I also keep track of the beads they were earning. This would help me gauge what changes I needed to make to keep them moving. Remember the end goal.

If these two boys didn’t already have an IEP, this change could be added to their RTI data showing a change in intervention. For myself and the classroom teacher, the goal is larger--we want them to grow as readers and not move into 3rd grade as nonreaders.

They still have a couple of weeks to go before I know if this work. I'll update you on their progress. The thing is that even if it doesn't work--it's made them better decoders and we’ll have new information to use to go forward with, to change the intervention and make it even more tailored to them and more specific to help them become independent fours.

I hope this idea gives you an idea on how to change things up and help get very specific about what students need to move. Make sure to grab a copy of the workbook to help guide you in making small data-driven decisions to move students within the RTI framework.

Until Next Time,

Why First Sound Fluency Matters? {Freebie}

Knowledge of letter-sound correspondences is essential in reading and writing

In order to read a word:

- the learner must recognize the letters in the word and associate each letter with its sound

- In order to write or type a word

- the learner must break the word into its component sounds and know the letters that represent these sounds.

What sequence should be used to teach letter-sound correspondence?

Letter-sound correspondences should be taught one at a time. As soon as the learner acquires one letter-sound correspondence, introduce a new one. I suggest teaching the letters and sounds in this sequence: a, m, t, p, o, n, c, d, u, s, g, h, i, f, b, l, e, r, w, k, x, v, y, z, j, q.

This sequence was designed to help learners start reading as soon as possible. Letters that occur frequently in simple words (e.g., a, m, t) are taught first. Letters that look similar and have similar sounds (b and d) are separated in the instructional sequence to avoid confusion. Short vowels are taught before long vowels. I teach upper case then lowercase. However, when I'm assessing the student they get both all the letters. (think DIBELS or AimsWeb Fluency probes.)

An example Instruction: For RTI and if I'm working 1 on 1 with a student. (I have had given this to para's or parents to do as well.)

Sample goal for instruction in letter-sound correspondences:

The learner will listen to a target sound presented orally identify the letter that represents the sound select the appropriate letter from a group of letter cards, an alphabet board, or a keyboard with at least 80% accuracy.

Instructional Task:

Here is an example of instruction to teach letter-sound correspondences. The instructor introduces the new letter and its sound shows a card with the letter m and says the sound “mmmm.” After practice with this letter sounds, then I review with the student.

The instructor says a letter sound.

The learner listens to the sound, looks at each of the letters provided as response options, selects the correct letter, from a group of letter cards, from an alphabet board, or from a keyboard.

Instructional Procedure:

The instructor teaches letter-sound correspondences using these procedures:

Model:

The instructor demonstrates the letter-sound correspondence for the learner.

Guided practice:

The instructor provides scaffolding support or prompting to help the learner match the letter and sound correctly.

The instructor gradually fades this support as the learner develops competence.

Independent practice:

The learner listens to the target sound and selects the letter independently. The instructor monitors the learner’s responses and provides appropriate feedback.

The Alphabetic Principle Plan of Instruction:

Teach letter-sound relationships explicitly and in isolation. Provide opportunities for children to practice letter-sound relationships in daily lessons. Provide practice opportunities that include new sound-letter relationships, as well as cumulatively reviewing previously taught relationships.

Give students opportunities early and often to apply their expanding knowledge of sound-letter relationships to the reading of phonetically spelled words that are familiar in meaning.

Amanda from Mrs. Richardson's Class has created a 20 minute Guided Reading Plan which I use with my Pre-A's and A's. The big piece is these guys are in books which is huge for them and makes their day.

Rate and Sequence of Instruction

No set rule governs how fast or how slow to introduce letter-sound relationships. One obvious and important factor to consider in determining the rate of introduction is the performance of the group of students with whom the instruction is to be used.

I tell the teachers I work with, think MASTERY. Start with the ones the student knows and then add no more than 5. Master and then add the next ones that make sense. Use your Probe data to drive your plan.

It is also a good idea to begin instruction in sound-letter relationships by choosing consonants such as f, m, n, r, and s, whose sounds can be pronounced in isolation with the least distortion. Stop sounds at the beginning or middle of words are harder for children to blend than are continuous sounds.

Instruction should also separate the introduction of sounds for letters that are auditorily confusing, such as /b/ and /v/ or /i/ and /e/, or visually confusing, such as b and d or p and g.

Many teachers use a combination of instructional methods rather than just one. Research suggests that explicit, teacher-directed instruction is more effective in teaching the alphabetic principle than is less-explicit and less-direct instruction.

FREEBIE TIME

POW: DRA Comprehension Rubric

I look at where the student scored on the rubric--taking note or strengths and weakness.

The Comprehension rubric is broken in 3 different skills--book knowledge, retell or summary, and higher order thinking questions.

In this case, a strength the student has is his book knowledge. With this book, it includes using the non-fiction text features as well. He struggled with retelling and the higher order thinking questions. (This would be a great jumping off put to collaborate with SLP to provide extra language support.)

As I'm planning out the Retelling Skill Lessons, I keep in mind grade level expectations--no book but then I think about what skills the student(s) needs to get there. I also keep in mind, when teaching comprehension skills I may need to get easier books to work with. I scaffold out the list of lessons so I can see what I'm thinking:

1) Modeled: without resource making sure to reference back to the rubric (at least a couple of days over a couple of different books)

2) Modeled: with pictures from the resource to create a Flow Map (at least of couple of days over a couple of different books)

3)Shared: with pictures (if you are doing most of the thinking then go back to a modeled lesson)

4) Shared: with pictures (moving them to independent thinking)

5) Independent with support using the book or resource to retell.

I will need to make sure the student's score 4s before starting the process over with student created drawings.

Why spend the time teaching retelling a story using student created drawings? Because it is a more appropriate grade level skill plus students will come across books with fewer and fewer pictures as they move to harder text. Student created drawings can be used across all curriculum areas and move the student to take control of what they need to access the curriculum--self-determination at its finest.

The last step is to start teaching the skill. I will plan on reassessing the comprehension part of the whole DRA rubric using the blank DRA forms in four weeks to see if the student has made growth. If so than I would teach, how to answer the Higher Order Thinking questions at the bottom of the comprehension rubric or I will plan on reteaching retelling/summaries again. I love using the Reading Comprehension Stems I've shared below. It's a great jumping off point when I work on comprehension skills. I use them for progress monitoring both in writing and in conversation. If you're have not signed up for my Free Resource Library, click here. (Its super easy and besides did I mention it was free to join. Who doesn't love free!)

I'd love to hear about your favorite reading comprehension teaching strategies. Pictures and my bad draws always seem to make students laugh and grow as a reader.

Until next time,

Letter-Sound Correspondence

What are letter-sound correspondences?

Letter-sound correspondences involve knowledge of:

- the sounds represented by the letters of the alphabet

- the letters used to represent the sounds

Why is knowledge of letter-sound correspondences important?

Knowledge of letter-sound correspondences is essential in reading and writing

- In order to read a word:

- the student must recognize the letters in the word and associate each letter with its sound

- In order the student must break the word into its component sounds and know the letters that represent these sounds.

What sequence should be used to teach letter-sound correspondence?

Letter-sound correspondences should be taught one at a time. As soon as the student acquires one letter sound correspondence, introduce a new one.

I tend to teaching the letters and sounds in this sequence

- a, m, t, p, o, n, c, d, u, s, g, h, i, f, b, l, e, r, w, k, x, v, y, z, j, q

- Letters that occur frequently in simple words (e.g., a, m, t) are taught first.

- Letters that look similar and have similar sounds (b and d) are separated in the instructional sequence to avoid confusion.

- Short vowels are taught before long vowels.

- I tend to teach lower case letters first before upper case letters. Pick one and stick to it.

- prior knowledge

- interests

- hearing

Start by teaching the sounds of the letters, not their names. Knowing the names of letters is not necessary to read or write. Knowledge of letter names can interfere with successful decoding.

- For example, the student looks at a word and thinks of the names of the letters instead of the sounds.

The student will:

- listen to a target sound presented orally

- identify the letter that represents the sound

- select the appropriate letter from a group of letter cards, an alphabet board, or a keyboard with at least 80% accuracy

Instructional Task

Here is an example of instruction to teach letter-sound correspondences

Teacher

- introduces the new letter and its sound

- shows a card with the letter m and says the sound “mmmm”

After practice with this letter sound, the instructor provides review

Teacher

- says a letter sound

- listens to the sound

- looks at each of the letters provided as response options

- selects the correct letter

- from a group of letter cards,

- from an alphabet board, or

- from a keyboard.

Instructional Materials

Various materials can be used to teach letter-sound correspondences

- cards with lower case letters

- an alphabet board that includes lower case letters

- a keyboard adapted to include lower case letters

- listen to the target sound – “mmmm”

- select the letter – m – from the keyboard

Instructional Procedure

The teacher teaches letter-sound correspondences using these procedures:

- Model

- The teacher demonstrates the letter-sound correspondence for the student.

- Guided practice

- The teacher provides scaffolding support or prompting to help the student match the letter and sound correctly.

- Independent practice

- The student listens to the target sound and selects the letter independently.

- The teacher monitors the student’s responses and provides appropriate feedback.

Pointers

There are a wide range of fonts. These fonts use different forms of letters, especially the letter a.

- Initially use a consistent font in all instructional materials (I use one that have the capital I and lower case q-I want.)

- Later, I introduce variations in font.

What are Best Practices in Phonics Instruction?

Phonics instruction has become the most controversial of all areas of reading education over the last ten years. Phonics has become my main stay in small group instruction. Once the only aspect of reading instruction, it has now become one of five important components of reading education (with phonemic awareness, reading comprehension, vocabulary instruction and fluency building making up the other four areas). Phonics builds a strong literacy foundation.

Phonics instruction has become the most controversial of all areas of reading education over the last ten years. Phonics has become my main stay in small group instruction. Once the only aspect of reading instruction, it has now become one of five important components of reading education (with phonemic awareness, reading comprehension, vocabulary instruction and fluency building making up the other four areas). Phonics builds a strong literacy foundation.Timing and Grouping

Phonics instruction provides the most benefit for young readers. The critical period for learning phonics extends from the time that the child begins to read (usually kindergarten) to approximately three years after. In studies, children receiving phonics instruction starting in kindergarten and continuing for two to three years after saw the greatest gains in learning and applying phonics to reading tasks.Phonic instruction for young readers can be offered in any grouping configuration. There was no notable difference in children receiving instruction one-on-one, in small groups or as a whole class. The most influential components were the age of the students and the instructional format.

Systematic Instruction

The best way to teach phonics is systematically. This means moving children through a planned sequence of skills rather than teaching particular aspects of phonics as they are encountered in texts. Systematic instruction can focus on synthetic phonics (decoding words by translating letters into sounds and then blending them), analytic phonics (identifying whole words then parsing out letter-sound connections), analogy phonics (using familiar parts of words to discover new words), phonics through spelling (using sound-letter connections to write words) and/or phonics in context (combining sound-letter connections with context clues to decode new words). Regardless of the specific method used what is most important in systematic instruction is that there is a deliberate and sequential focus on building and using the relationship between sounds and letter symbols to help readers decode new words.Modeling Followed by Independent Practice

Because the connection between letters and sounds is not readily apparent to new readers, modeling is an important aspect of phonics instruction. Both teachers and parents should model ways that a reader uses the sound-symbol relationship to decode unfamiliar words by reading and thinking aloud. The best texts for modeling are high interest or informational. These include (but are not limited to) nursery rhymes, songs, non-fiction books and poems with repetitive language.Once children have been exposed to adult modeling several times, they should be encouraged to practice applying phonics to their own reading. This independent practice helps young readers truly build the connection between symbols and sounds. Adults should guide children in strategically applying phonics to authentic reading and writing experiences to help them develop good decoding skills.

Literature-Based Instruction

For many years phonics was taught in isolation. Worksheets or textbook that asked them to decode and write lists of words is not the answer. Researchers discovered that young readers could not apply the decoding skills “learned” in isolation to real reading tasks such as reading a story or a book. It is now recommended that phonics be taught through literature. While this may seem contrary to the systematic approach to instruction, it is not. Teachers and parents should select pieces of age and developmentally appropriate literature that highlight the phonics skills focused on at particular points in the sequence of instruction. For example, if children are learning to identify the sound-letter connection in /b/ an appropriate piece of literature to teach and reinforce this skill would be one that uses alliteration (repetition of beginning sounds) of the /b/ sound. Plus it helps with skill transfer.

Individualized Approach

Individualized Approach

Because students come to kindergarten at a variety of different reading readiness levels, it is important that teachers assess where students are at and individualize their phonics instruction. One student may begin the year already knowing single letter sound-letter connections making her ready to work on blends. Another student may have very little phonemic awareness and exposure to print texts. Therefore teachers must tailor instruction to meet each student’s needs. This ensures they will continue to develop appropriate phonics skills.Home-School Connections

As with every academic area, parental involvement is one of the keys to success. This is especially true for reading development. The more a parent can read with a child at home, the better chance she has of developing a strong interest in and ability to read. Parents should reinforce phonics as they read at home with their children. Modeling phonics use to decode unfamiliar words and guiding children as they attempt to apply these strategies to their independent reading helps them develop as readers. Teachers can help parents by providing information on phonics and how to use the sound-letter connection to decode words.

As with every academic area, parental involvement is one of the keys to success. This is especially true for reading development. The more a parent can read with a child at home, the better chance she has of developing a strong interest in and ability to read. Parents should reinforce phonics as they read at home with their children. Modeling phonics use to decode unfamiliar words and guiding children as they attempt to apply these strategies to their independent reading helps them develop as readers. Teachers can help parents by providing information on phonics and how to use the sound-letter connection to decode words.

What are the Six Syllable Types?

Why teach syllables?

Closed syllables

Vowel-Consonant-e (VCe) syllables

Open syllables

Vowel team syllables

Vowel-r syllables

Consonant-le (C-le) syllables

Have a gerat week!

October Pinterest Linky Party

The last couple of months have been crazy. One thing that teachers have been hitting me up for is Sound and Letter Identification ideas. A couple of activities that my small group students love are below.

The last couple of months have been crazy. One thing that teachers have been hitting me up for is Sound and Letter Identification ideas. A couple of activities that my small group students love are below.

I love this pin because she thinks outside the box and has ideas that are not used every day in a classroom. This is great for a teacher that has tried everything and needs new ideas.

Have a great weekend!

What is Phonemic Awareness?

Before children learn to read print, they need to become aware of how the sounds in words work. They must understand that words are made up of speech sounds, or phonemes.

Before children learn to read print, they need to become aware of how the sounds in words work. They must understand that words are made up of speech sounds, or phonemes.- recognizing which words in a set of words begin with the same sound ("Bell, bike, and boy all have /b/ at the beginning.")

- isolating and saying the first or last sound in a word ("The beginning sound of dog is /d/." "The ending sound of sit is /t/.")

- blending the separate sounds in a word to say the word ("/m/, /a/, /p/ – map.")

- segmenting a word into its separate sounds ("up – /u/, /p/.")

- Attending to unfamiliar words and comparing them with known words

- Repeating and pronouncing words correctly

- Remembering (encoding) words accurately so that they can be retrieved and used

- Differentiating words that sound similar so their meanings can be contrasted

Oral Language Development

At the beginning of the school year, students need to know key phrases and expressions that they can use to communicate with teachers and students during the school day. Being able to communicate effectively with others is key for learning to take place. With some work, students can develop the type of everyday communication skills that facilitate learning. This strategy called Total Physical Response to help students in these early stages of language development.

Learning key phrases through Total Physical Response

Total Physical Response (TPR) activities greatly multiply the language input and output that can be handled by beginning English language learners (ELLs). TPR activities elicit whole-body responses when new words or phrases are introduced. Teachers can develop quick scripts that provide ELLs and other students with the vocabulary and/or classroom behaviors related to everyday situations. For example, "Take out your math book. Put it on your desk. Put it on your head. Put it under the chair. Hold it in your left hand."You will see them talk sooner when they are learning by doing. TPR activities help students adjust to school and understand the behaviors required and the instructions they will hear. This will help them in mainstream classrooms, in the halls, during lunchtime, during fire drills, on field trips, and in everyday life activities.

Strategies: How to use Total Physical Response

There are seven steps for the TPR instructional process:1. Introduction

The teacher introduces a situation in which students follow a set of commands using actions. Usually props such as pictures or real objects accompany the actions. Some actions may be real while others are pretend.

2. Demonstration

The teacher demonstrates or asks a student to demonstrate this series of actions. The other students are expected to pay careful attention. At first, students are not expected to talk or repeat the commands. But soon they will want to join in because the commands are easy to follow and the language is clear and comprehensible. For example, the teacher gives a command such as "Take out a piece of bread" and the students say the sentence and do the action. "Now, spread peanut butter on it", and so on until a make-believe sandwich is made and eaten.

3. Group action

Next, the class acts out the series while the teacher gives the commands. Usually, this step is repeated several times so that students internalize the series thoroughly before they will be asked to produce it.

4. Written copy

Write the series on the chalkboard or chart paper so that students can make connections between oral and written words while they read and copy (or even substitute ingredients of their choice).

5. Oral repetitions and questions

After students have made a written copy, they repeat each line after the teacher, taking care with difficult words. They ask questions for clarification, and the teacher points out grammatical features such as "Yesterday we ate half a sandwich. Today we will eat a whole sandwich. Did you notice the difference between ate and eat? Yesterday we spread grape jelly, today we will spread orange jelly. Did you notice that the verb spread didn't change? Let's say the words soap and soup. Let's say the words cheap and sheep."

6. Student demonstration

Students can also take turns playing the roles of the reader of the series and the performer of the actions. Meanwhile, the teacher can check on individual students for comprehension and oral production.

7. Other activities

- Use pictures from magazines, the Internet, pictures books. And have students talk about them. Let them take the lead.

- Before reading a children's story, select some action words and ask the students to perform these actions as you encounter them in the pages. List them on the chalkboard.

- After reading the story, ask children to summarize the story by acting out the words you have demonstrated.

- After reading the story, ask the children to select some words or phrases that they would like to turn into actions.

Text Access Ideas for Below Grade Readers

Like many my daily schedule is already jam-packed, and it's challenging to add one more thing. Here are three ideas that won’t take a lot of extra time and will support your striving readers as they move toward reading independently and comprehending increasingly complex texts.

1. Read aloud texts that may be challenging, providing all students the opportunity to boost their comprehension and engage in collaborative conversations.

Reading aloud is such an integral part of my daily instruction that my students and I keep a read-aloud tally (pictured below), using one tally mark for each read-aloud experience. The essential literacy practice of reading aloud is also endorsed by the authors of the Common Core's ELA Standards in Appendix A (p. 27). I do the grade level reading and grade vocabulary works as a read aloud and ask higher order thinking questions.

2. Guide readers individually and in small groups. To make the most of the time you will spend guiding readers one-on-one or in small groups, it is wise to pinpoint their strengths and areas of need. The best way to do this is by using a reading assessment that includes a running record. This will enable you to know your students' instructional level and, as important, whether your readers are struggling with decoding, fluency, vocabulary or comprehension. Armed with this information, meet with students as often as possible to prompt and coach them to apply decoding strategies for figuring out unknown words and comprehension strategies to better understand the text. If your reading program provides leveled texts, these will work well for guiding readers in small group. I spend three days a week working as a guided reading group, where we read instructional level text. I always have a written assignment on these days to push them to use the resource (spelling, sighting text).

3. I have a couple of students that this is not enough for them to access the material. So I use Boardmaker and Google Images to highlight the key part of the text in a picture based sentence strip. I tape the strip on the the story, so that the students have the original text but can read the sentence that I added to understand the text.

I hope these ideas help you in the classroom. I've been playing with student access and have created a couple of adaptive books for a student who is working on her shapes and colors. Enjoy them free below.

About Me

Resource Library

Thank you! You have successfully subscribed to our newsletter.